The trip was not planned. As concerns over the spread of Covid-19 grew and the country inched more and more towards the abnormal, I figured travel might be restricted before the end of the week. A call that Tuesday morning confirmed that feeling: I decided to travel out of Abuja immediately.

What I saw at the airport and on the flight on the short trip to Lagos, was a special class on the current public health crisis. I kept thinking…

Of the numerous, dizzying changes that have come upon us in recent times, one that we have had to quickly adapt to is the new social word register. New words have emerged that have fundamentally – and maybe forever – changed the way we work, play and relate to each other. Social protocol may never be the same again even long after Covid-19 has subsided or passed.

Take the word, “social distancing”, for example. According to experts on public health, “Social distancing is for healthy persons, to prevent them from coming in contact with infected persons and contracting the disease.”

Social distancing stands everything we know about how we live on its head. We live together, work together, play together and pray together. There’s no clearer expression of this social norm than in the transport systems and the face-me-I-face-you design of many houses in urban areas. Afro-beat maestro, Fela, captured it aptly in “Suffering and Smiling”, where 49 passengers would be sitting in a bus, and 99 standing without complaining.

Also, a welcome is incomplete without a heart-hug. When we’re in line, we tend to press each other from behind, breathing hot air on the shoulders of the person in front and pressing hard, bonnet-to-bumper.

Five people would easily squeeze themselves onto a seat meant for three and should anyone dare to complain, the complainant would be reprimanded that one body does not avoid another. If any space can take one, then it can take two. And if it can take two, it can take three.

Social hugging could be hugely inconveniencing and even repugnant in a few cases, but the motive or value wasn’t always bad. In situations where government is almost completely absent, the communal spirit was the only social safety net to depend on.

Ostracism, which is perhaps the social equivalent of “social distancing”, was invoked in extreme cases of communicable diseases or to punish “social abomination.”

But the public health call for social distancing does not discriminate. On this trip to Lagos, I noticed a clear difference in distancing not just at the ticketing lines, but surprisingly, at the departure lounge, where packing each other like sardines used to be passenger’s pastime.

In what looked more like ostracism than social distancing, passengers sat significantly far apart from one another, with only those who appeared to be families huddling closer. And in a few cases where someone was moving too close in defiance of multiple visual daggers thrown at them, the passengers they were moving too close to simply stood up, and moved elsewhere.

When we approached the boarding gate, airline staff who used to have a hard time getting passengers to stand in line for boarding, were actually begging passengers who had left unusually large distances between themselves, to move a bit closer and come forward quickly for boarding.

I don’t know how much longer this situation would last but I hope we can take useful lessons about respect for decent personal space and when all is said and done, also maintain a healthy social distance from paranoia.

The cabin looked like a huge floating hospital theatre with well over half the passengers wearing face masks and all sorts of medical gear. Quite a number of the passengers were also wearing hand gloves, apart from face masks. Perhaps if they could find the full personal protective equipment, they would have had no hesitation buying them, even at a premium, and wearing them.

I felt a bit awkward and out of place as I took my seat near the back, beside a young man, who just like me, had virtually no protective wear.

I had toyed with the idea of travelling by road but changed my mind. A friend, who suspected that my decision may have been influenced by safety, said I didn’t need to worry about kidnappers or robbers at this time. Didn’t I notice that reports of kidnappings had reduced remarkably?

He suggested that kidnappers and other bad people were not only observing “social distancing” since they didn’t know if their victims were infected or not, perhaps they could not afford face masks and other protective gear which might have helped them to reduce the risk in the “business”. Whatever the case, I didn’t want to find out. But sitting here on this flight and looking like fish out of water, I was wondering if flying was the right decision after all.

The cabin crew also had face masks and gloves, but yet warned passengers not to touch any crew members. Passengers were advised to use the call bell if they needed anything. Don’t touch crew members.

But come to think of it, what is the standard advisory about the correct use of face masks?

WHO says on its website, that, “If you are healthy, you only need to wear a face mask if you are taking care of a person with suspected 2019-nCovid infection. Wear a mask if you are coughing or sneezing.”

So, why am I surrounded by a sea of mask-wearing passengers and crew. It’s either some of them have something to hide behind their masks – or I have something to worry about! Either way, it left me with an eerily feeling.

Just before take-off, I received a message that Vice President Yemi Osinbajo had gone into “self-isolation.” That was concerning. Osinbajo had been in meetings with Chief of Staff, Abba Kyari, who had tested positive to the virus. So, there were concerns for the Vice President’s health and safety, for which he had to move into separation as a precautionary step.

But what does “self-isolation” mean? Our daily use of the word may permit some latitude, but the news that Osinbajo was in “self-isolation”, sent a wrong message from what was intended. To say he is in “self-isolation”, means that he has contacted the virus; which obviously was not the case.

He was in quarantine, which means he is well and needed to separate himself to avoid infection.

The National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) might do well to advise the raft of public officers declaring that they are in “self-isolation”, to be clearer about what they are saying. As long as they keep confusing “isolation” with “quarantine”, they will leave the public confused about what to know and believe.

So, Covid-19 concerns have forced a partial lockdown of the Presidential Villa? We have seen from the last few weeks that lockdown means different things in different places.

In Italy, Spain and a number of European countries, for example, lockdown means lockdown: no movement outdoors except with authorised permit and stay-at-home orders enforced by the military. In the UK, lockdown means highly restricted movement, with few exceptions made for the park and purchase of staples on a ration.

In Nigeria, we are still trying to find out what lockdown means beyond restrictions on social and religious gatherings and closure of schools, international airports and the land borders. When we do, it might well be that even local flights are a dangerous luxury in a country where a national lawmaker would remove his face mask to sneeze when the Senate is in session!

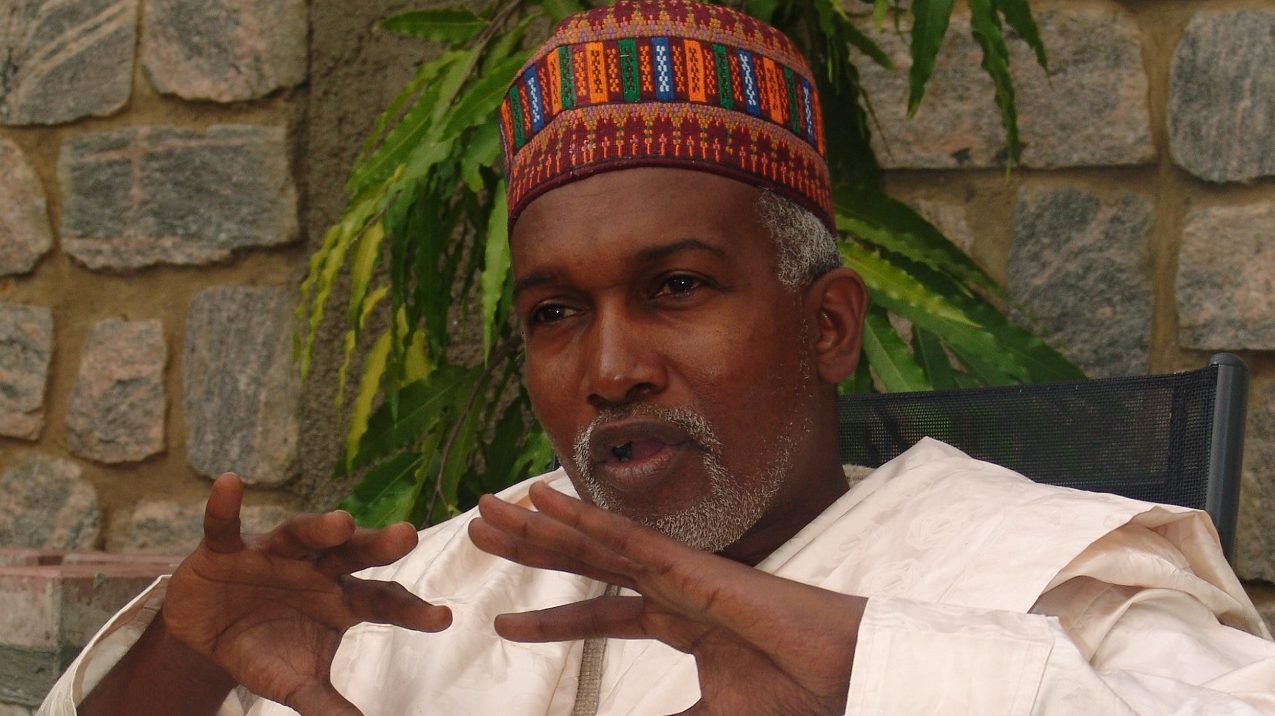

Ishiekwene is the MD/Editor-In-Chief of The Interview