Brutal beatings and rising inflation are proving a noxious mix in Zimbabwe, writes the BBC’s Andrew Harding.

In a long queue for rationed bread, on the pavement outside a supermarket, two women watched an approaching foreign journalist with trepidation.

“Please don’t show our faces,” said the taller woman. “We’re afraid. We’re living in ‘scare-ity’.”

Just ahead of them in the queue, a man who also didn’t want to give his name, spoke of the humiliation of being forced to wait in the rain, for more than an hour, to feed his family.

“There is scarcity of bread,” he complained.

“Scare-ity” and scarcity are two words that seem to sum up Zimbabwe’s current predicament.

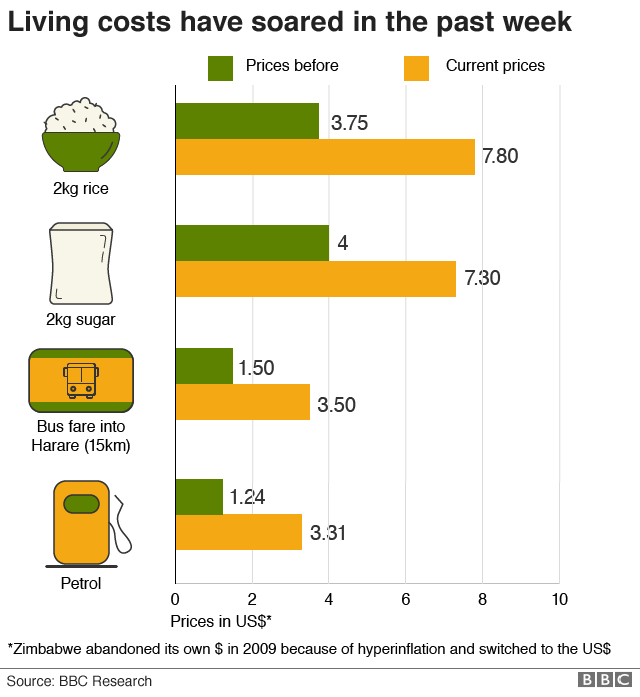

This is the aftermath of last week’s violent protests against the rising cost of living, triggered by a more than doubling in the price of fuel.

A brutal and ongoing security clampdown by the police and army has left many here fearful that the country is quickly sliding back to the worst authoritarianism of the era of former President Robert Mugabe, who was ousted in November 2017 after 37 years in power.

“I need vegetables, salt, flour, cooking oil… no luxuries,” said primary school teacher Charles Chinosengwa, who was adding up his monthly budget on a spreadsheet, explaining that his salary no longer covers even a third of what his family needs.

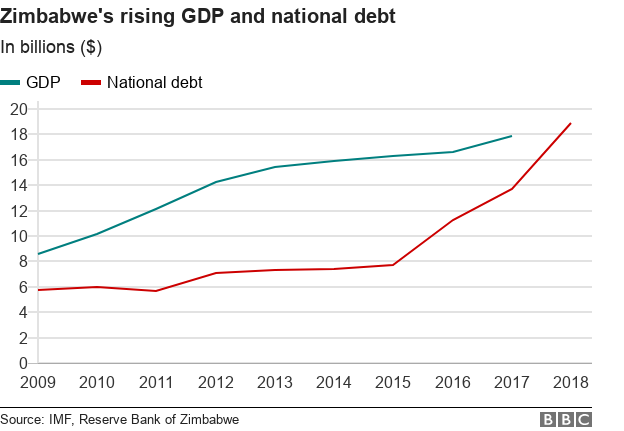

The government pays salaries in an electronic currency – bond notes – which is supposedly pegged, one-to-one, to the US dollar. But in the real economy its value has plummeted as confidence in the Zanu-PF-led government’s economic reform programme collapses.

Austerity in Zimbabwe

- The government introduced austerity in October 2018 to reduce government debt and stabilise the economy

- Government spending was cut and new taxes introduced

- Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube said there would be “pain and sacrifice”

“Let’s not even talk about the fact that people are angry – people are desperate,” said David Dzatsunga, who heads an association representing Zimbabwe’s college lecturers.

“They are supposed to continue to come to work, but the money they are earning is not enough for transport. They can’t pay school fees. Their children are sitting at home.

“Really, it’s more about desperation than anything else.”

In hiding

But what’s unclear is whether that desperation will inevitably lead to more public protests – and perhaps more violence – or whether Zimbabweans may now be too scared to challenge the authorities again.

On the impoverished, crowded outskirts of Harare, in suburbs like Epworth, the anger is still palpable.

Most people here support the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) and believe last year’s presidential election was stolen by Zanu-PF.

Among those who joined last week’s protests was a 53-year-old nursery school headmistress, Thandiwe Ncube. She was hit and killed by an army truck.

A dozen children were playing outside the Cheer-up School – a dilapidated building with a tin roof – when I visited.

Ms Ncube’s daughter, Ellen Ngwenya, said most of the children’s parents could no longer afford to pay the fees.

“I blame the government [for my mother’s death] because if the economy was OK she wouldn’t protest. We’ll continue protesting until things settle,” she said.

“I’m not afraid to protest, because we are hungry.”

But many of the protest leaders, activists and union representatives have now been detained and denied bail.

Others are in hiding.

‘Co-ordinated suppression’

Harare lawyer Kudzayi Kadzere believes the state is conspiring – to a degree rarely seen even under President Mugabe’s rule – to silence dissent.

“We have seen a pattern of co-ordinated action between the army, the police, the prosecution and the courts,” Mr Kadzere said.

“It is to suppress the voice of the people who want to express their anger at the deteriorating conditions in the country.”

He argued that the army’s prominent role in the crackdown is of particular concern.

“We are seeing more and more of the military coming out in the open and being involved. They have not retreated to the barracks.

“In Zimbabwe it is not usual for you to come across uniformed soldiers, so for us to see soldiers each and every day moving around in their trucks is quite chilling.”

‘Hard side of the law’

At State House, the government of President Emmerson Mnangagwa insists the international criticism is disproportionate. It says that any “excesses” by the security forces should be set beside the violence of demonstrators.

More on Zimbabwe

- The most expensive fuel in the world?

- No cash, no bread, no KFC amid new Zimbabwe crisis

- Why Zimbabwe’s Christmas crackers cost $40

“Anyone who strays from the path of law and order necessarily invites the hard side of the law,” said the president’s spokesman George Chiramba.

“Naturally when [our security] forces react to that kind of lawlessness… It is not a science, it is not calibrated, there is always that element of excesses.”

But the prominence of the army in the crackdown – video footage obtained exclusively by the BBC showed troops beating civilians on the edge of Harare on Tuesday – continues to raise questions about the balance of power in the government.

Especially whether the generals who ousted Mr Mugabe and brought President Mnangagwa to power are still pulling the strings in the background.

For now, it seems, Zimbabwe is entering a lull, as the government seeks to shift the focus to its economic reform programme and the opposition rejects what it sees as a disingenuous offer of national dialogue from the presidency.

In recent months, Mr Mnangagwa has frittered away much of the goodwill he enjoyed in the aftermath of his predecessor’s removal, and heady promises of a new Zimbabwe that would be “open for business”.

But there are still plenty of Zimbabweans who are ready to give the government the benefit of the doubt, and who believe that the short-term pain of austerity measures may eventually lead to an economic revival.

“They have a plan but I think we’ve just got to let this government settle down and do what they need to do… without some side tracking,” said Carol White, managing director of the Meikles Hotel in Harare.

‘Bloated government’

Others are less optimistic. Local economist John Robertson is scathing about the government’s claim that Zimbabwe is on the mend.

“Well, we’re open for investment, but under conditions that are found by investors to be the least attractive in the world,” he said.

“Hundreds of thousands of people in government appear to have no purpose other than to extract money in the form of fees for license and permits,” he added, arguing that Zimbabwe’s corrupt and bloated government is making the public suffer, but is not serious about tightening its own belt or cutting red tape.

“They’re standing in the way of business. Government is holding up the progress, and does not want to see the size of government reduced so that the budget deficit could be something we could live with.

“I wish I could paint a better [picture]. But these are the facts as I see them.”

Source: BBC