Sometimes a piece of literature overtakes the world and all her busy schedules and start drawing attention for itself. You remember when The Critique of Pure Reason, a book written by the great German philosopher, Immanuel Kant, first made its appearance on the intellectual scene. The reception was more than phenomenal. World leaders, academia, aristocrats and even peasants, friends and foes were reaching out to grab a copy. Institutions of learning were contracting the size of their curriculum, to secure a fitting adjustment for the book. Language barriers were pared down as copyright waivers were sought, to give the book a multilingual status. Why the sensation if one may ask? For those abreast with the history of Western intellectual thought, this question is enough recipe for the most fiery of eloquence. This is because, from the earliest development of philosophical thought, to the rise of philosophical dialectics, no work has ever charged the intellectual climate like Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. The book was at once revolutionary and groundbreaking. And as rightly expected, the world’s reaction to it was not that of levity or flippancy but of a head on collision with the greatest exigency of the then literary world. There were paradigm shifts, checks and balances, rulings and reversals, twist and turns and other revolutionary trends to boot. For the first time in the history of western thought, the epistemological confidence of the Continental rationalists and the British empiricists began to look frail. The resolutions they have built for years began falling in. What is more? Epistemology will never be the same again because Kant has lived. However, what is of greatest relevance is not that Kant unseated the prevalent epistemological outlook, but that he brought philosophers out of their extreme simplicity of intellect and gave them another chance to review their epistemological convictions, to avoid smugness. The book it must be seem was a call for revolution. It was indeed a revolution which according to Kant approached Copernican dimension. Interestingly, philosophers instead of agitating, proved their resilience in the face of that, which seemed like a wholesale deconstruction and redesigning of their ancient stand on epistemology. What other better way can one begin to broach Achebe’s new book, There Was a Country, than the much the above preface has claimed? This is how I will temper the flow of this literary piece.

Sometimes a piece of literature overtakes the world and all her busy schedules and start drawing attention for itself. You remember when The Critique of Pure Reason, a book written by the great German philosopher, Immanuel Kant, first made its appearance on the intellectual scene. The reception was more than phenomenal. World leaders, academia, aristocrats and even peasants, friends and foes were reaching out to grab a copy. Institutions of learning were contracting the size of their curriculum, to secure a fitting adjustment for the book. Language barriers were pared down as copyright waivers were sought, to give the book a multilingual status. Why the sensation if one may ask? For those abreast with the history of Western intellectual thought, this question is enough recipe for the most fiery of eloquence. This is because, from the earliest development of philosophical thought, to the rise of philosophical dialectics, no work has ever charged the intellectual climate like Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. The book was at once revolutionary and groundbreaking. And as rightly expected, the world’s reaction to it was not that of levity or flippancy but of a head on collision with the greatest exigency of the then literary world. There were paradigm shifts, checks and balances, rulings and reversals, twist and turns and other revolutionary trends to boot. For the first time in the history of western thought, the epistemological confidence of the Continental rationalists and the British empiricists began to look frail. The resolutions they have built for years began falling in. What is more? Epistemology will never be the same again because Kant has lived. However, what is of greatest relevance is not that Kant unseated the prevalent epistemological outlook, but that he brought philosophers out of their extreme simplicity of intellect and gave them another chance to review their epistemological convictions, to avoid smugness. The book it must be seem was a call for revolution. It was indeed a revolution which according to Kant approached Copernican dimension. Interestingly, philosophers instead of agitating, proved their resilience in the face of that, which seemed like a wholesale deconstruction and redesigning of their ancient stand on epistemology. What other better way can one begin to broach Achebe’s new book, There Was a Country, than the much the above preface has claimed? This is how I will temper the flow of this literary piece.

Towards the end of 2012, a book published in far away America was charging the political climate of Nigeria. Achebe’s There Was a Country made its appearance on the intellectual scene, at a time when Nigeria’s political system, seemed to be coming apart at the seams. There were religious cum ethnic crisis, security challenges, Boko Haram insurgency and a lot of other social strains. A country whose endurance nerves, have been frayed, battered, assaulted and even stretched almost to the crack of doom, by all these exigencies, Achebe’s indictment of Awolowo and Gowon as wartime criminals, became nothing but an assault taken too far. And as mostly expected, Achebe’s critics swooped on him, almost with the fury of a wounded lion. The way the critics reduced the book to Gowon and Awo issue, as if that was the only thing the book sets out to tackle, has no parallel in the annals of publishing precedent. But one can fairly parallel the scenario to the manner with which Greek warriors reduced Trojan city to rubbles. Though Greek warriors stood for ten years outside the Trojan wall, baying for the Trojan blood, the decade in years could not bring abatement to their fury and rancour, rather it added maturity and venom to their rage. Unfortunately, the very moment Greek warriors penetrated the Trojan wall, Trojans suffered the fury that could only come from a pent up anger. This is exactly the fate that seems to be the lot of Achebe’s new book.

Yes! Achebe’s critics seem to be coming from the background of a long held grudge, against a man who has said a lot of unflattering things about his country and his people. Think of his rejection of the offer of a national award from the Nigerian government. Just like Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar rejected the kingly crown offered to him by the Romans, Achebe had on two occasions rejected the offer of a national honorary award from the government of Nigeria. What of his powerful book titled The Trouble With Nigeria where he berated the leaders of Nigerian government for their poor leadership skill? All these could be more than enough to put one at daggers-drawn with his country. And yet here he comes again with a new book, chronicling Nigeria’s bleak and harrowing past, condemning both the living and the dead, ravaging ethnic sensibilities and opening up old wounds as well as the stage for throwing of invectives. Now why does Achebe matter so much to Nigeria and her affairs? Why is the old man difficult to be ignored? What pact has he with Nigeria that makes every of his statement an issue for national debate?

In trying to give vent to Achebe issue, my mind readily goes to an author who gave an expression that cuts my imagination. According to him, when an issue is discussed and passed on but does not cease to attract attention, one expects that it has a genuine problem but an unsatisfactory solution. The issue of Achebe’s criticism of Nigeria’s political shenanigan, raising serious political dust has never ceased to recur. The antagonism that trails every of his gestures, is a proof to the fact that Achebe issue is a serious problem, but unfortunately has not been given a genuine solution. The back biting, throwing of tantrum and invectives that have long characterized Nigeria’s attitude toward Achebe issue can no longer hold water. It is either we face the man and his message squarely or ignore him to our peril.

The best way to face Achebe and his message squarely is to go historical. This is because according to Chimamanda, to begin the story of any people with the phrase ‘secondly’ is to end up with a different story. Achebe’s flair for remaining controversial in the affairs of Nigeria did not start with his rejection of national award or publication of his The Trouble With Nigeria. To plot it’s provenance from that end is to gloss over subtle facts that will do justice to history. Achebe’s knack for being controversial must have stemmed from the critical sensibility of a man, who unfortunately, sees his own beloved country, from the long perspective of impetuous vortex of chequered history. Therefore, we have to track Achebe down from the very point he started with Nigeria to enable us see his reasons for being controversial in the affairs of Nigeria.

Giving the historical instances of colonialism and its track record of fatalities, Nigeria and Africa at large were unfortunately in dire need of a redress. There was the need to tell our own story by ourselves. There was the need to buffet the stereotypical assumptions the westerners had about Africa as a continent of barbarism, cultural stagnation and darkness. Providentially, Achebe bought into the passion and set out to work on his Things Fall Apart. Things Fall Apart is not just about the tragedy of Ikemefuna and Okonkwo. After all what significance has the tragedy of two wild unknown men living in Umuofia, a remote and obscure hamlet, tucked away in the heart of Africa, hold for the world that has seen the horrors of two world wars and Hitler’s holocaust. No! Such trifles could not have sustained the endless flow of praises the book has been enjoying ever since its publication. For all its takes and reservations, Things Fall Apart remains, not just a priceless testament of human creative genius, but also a paradigm instance of literary avant-garde. Not only that it takes rank with few classics in the world, it also stands tall as the book that rallied the wider world to reread the African story. Armed with the annihilating power of intellectual dynamite, Things Fall Apart shattered the sediments of falsehood, prejudice, blackmail and other smug shots the West had been hauling on Africa, and left at its dregs, a continent made sunny, not just by the trappings of its tropical bearing from the equator, but also by a promising amount of its beautiful and resourceful cultural heritage. For the first time in her history, Africa towers as a continent peopled with creatures rich in the virtues of the soul. In the conventional slangs, Africa was just ‘the place’, thanks to the likes of Achebe.

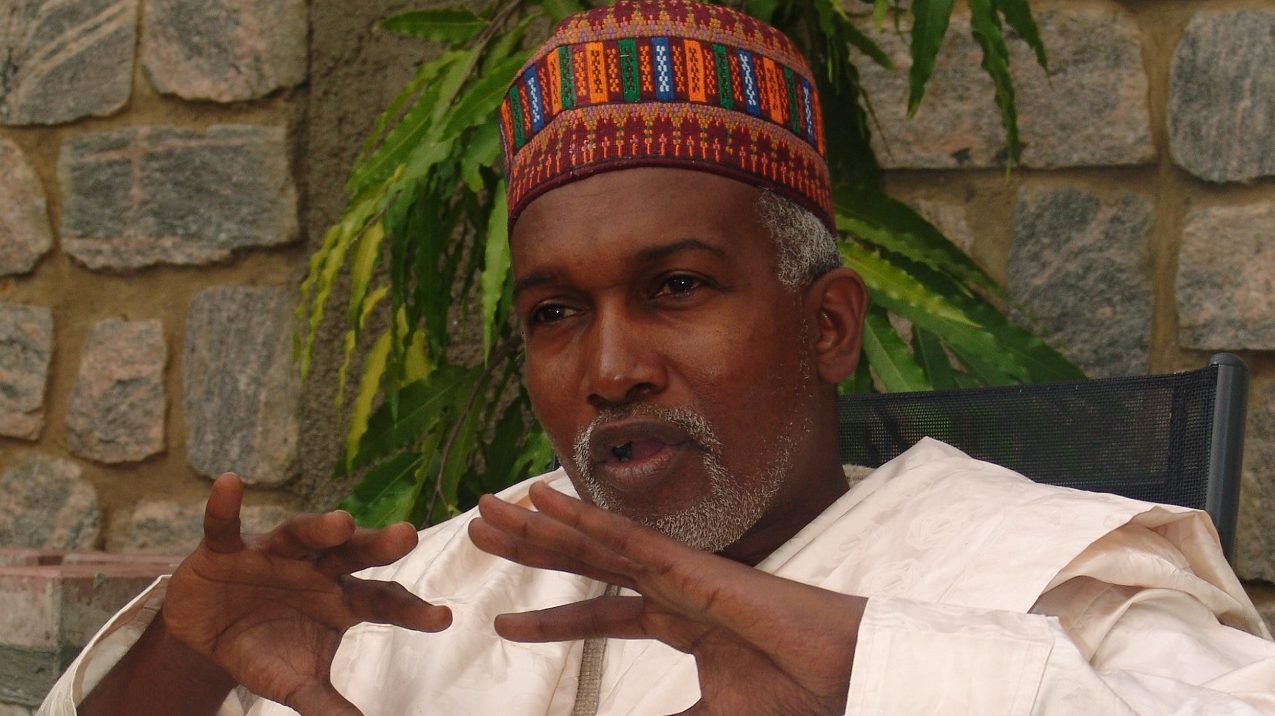

Things Fall Apart has a special place in the history of Nigeria. Coming barely two years before her birth as a nation, Nigeria could not but add it to the wave of optimism that graced her independence. Being recognized as the home country of Achebe, the literary legend, was for Nigeria an honour to be very proud of. It was like a birthday gift to a new born nation. Most Nigerians who travelled outside the country then, confessed to being treated to unsolicited favour, for merely going by the name Achebe or that of the novel’s tragic hero Okonkwo. The name Nigeria sounded fair and pleasing to the ears of the global world. It was indeed Nigeria’s golden age. And… oh this writer is yielding to emotion, as his sense of nostalgia comes to a grip, a sign of acute longing for a situation that is undoubtedly lost. It is just emotionally defeating, to contend with the fact that the Nigeria of our founding fathers, the giant of Africa, the land of the rising sun, of lovely people is no more. Achebe’s There Was a Country is just a way of expressing this fact, the painful fact that the very country in question is no more. Yes! I know Achebe meant Biafra, but the tragedy of Biafra is more than an Igbo affair. It is Nigeria’s collective tragedy. To deny this fact is to have me prove you wrong with the searing words of Martin Luther King Jr. According to him, Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied to a single garment of destiny. What affects one directly, affects all indirectly. Is it surprising then that Nigeria has not made much headway politically ever since Biafran saga? I doubt if anyone will answer in affirmation. So this is the past There Was a Country is calling us to address. It is the book’s greatest message. The justice has much been delayed but let it not be denied. There is no way we can end impunity and move forward as a nation, if the errors of the past are not addressed. The reason why impunity still skulks in Nigeria is because, there is no punitive precedent that serves as a deterrent for future offenders. I remember Hassan Kuka arguing that the saddest aspect of Nigeria’s politics, has been the absence of a coherent programme of transition dedicated to ending impunity, leading the nation to genuine democracy. The famous Nuremberg trials where the perpetrators of crime against humanity during Hitler’s Nazi regime were prosecuted gave birth to transitional justice. The trials of German and Japanese officers and other key perpetrators of the war were meant to send positive signals that would end impunity. The Nuremberg trials laid the foundation for the evolution of the culture of human rights as an integral part of the architecture of governance. There Was a Country reminds us of this woeful lack.

Therefore, for all those who are still criticizing or have criticized Achebe and his new book, I challenge you to look beyond the blurred prism of ethnic or whatever sentiment, to see the far reaches of the book. Chimamanda would have scored high in her attempt to stem the tide of criticism that has been trailing the book, had she not appealed to sentiments. She seeks to garner sympathy for Achebe by rallying all critics to acknowledge Achebe as a victim of war tragedy, a war survivor that has a terrible tale to tell. According to her, I wish more of the responses had acknowledged, a real acknowledgement and not merely a dismissive preface, the deep scars that experiences like Achebe’s must have left behind. To expect a dispassionate account from him is a remarkable failure of empathy. This is just an old cliché that appeals more to sentiments than reason. Hitler remains a villain, even though seasoned psychologists have come to throw about the tripe, that Jewish holocaust was just part of the trappings of his improvident background as a child. Why do men seek excuses for their crime but rarely offer one for their virtues? Humanity will never contend with those who will unleash havoc upon mankind just because they had terrible experience in the past. Origin if it must be understood is different from destiny. No one becomes bad simply because he is born by a bad mother. Come to think of it, Adam stood condemned in the sight of God even though he claimed Eve made him eat the fruit. Funny enough, Eve shifted the blame to the serpent. But that is not how God made us to live. Ours should be a life of responsibility for our actions. Achebe must tell us the truth and I believe he did that. It is better to suffer injustice than to do injustice.

What of Okey Ndibe who would like us to believe that Achebe has no right to say that Awolowo’s use of hunger as a war strategy was a means to advance his ambition for power? According to him; Whilst Achebe is justified in indicting Awo for espousing the use of starvation as a weapon, one wishes that he did not go as far as imputing a motive to the late Yoruba leader. When the author offers an “impression that Chief Obafemi Awolowo was driven by an overriding ambition for power, for himself in particular and for the advancement of his Yoruba people in general,” he opened himself to charges of speculative overreach. Awo supported a horrific policy; his motive – unless he confessed it in a document or to some confidant – is a different matter altogether. What is really disturbing here is where the speculation lies not to talk of its overreach. What better explanation will Okey give about a man who approaches him menacingly with a sharp cutlass? Should he wait for the man to confide in him that he has actually come to kill him before he can know that the man meant danger? Could it be speculation if I run away from such a man with the feeling that the man meant to kill me even though he didn’t say that? Okey should know that what defiles a man is not what enters him but what comes out of him. But he can still wait for Awo to come and explain the motive behind his baleful statement before he can know that a man with such a statement meant evil. As for me, if actually he said that, then I concur with Achebe, that history which neither personal wealth nor power can pre-empt, will pass terrible judgement on us, pronounce anathema on our names when we have accomplished our betrayal and passed on. Awo has accomplished his betrayal and as such deserves the light history has cast on him through Achebe’s new book.

Finally, Achebe has no need of any empathy from us. To reduce There Was a Country to a call for empathy as Chimamanda has done, is to lose sight of the greater merit of the book. The book should rather be seen as a national call from a great patriot for us to rewrite our history. As Things Fall Apart rebranded our image in the global world, There Was a Country has also the power to rebrand that image that has been marred. We must really be grateful to God for this final gift from a man who carried our course even before we were born as a nation and most especially now that we are dying as a nation.

jienislaw@yahoo.com