In over two decades since Nigeria’s return to constitutional democracy, this is the longest politicians have had to campaign before a general election. And that is a good and bad thing.

It’s good because it is giving politicians a longer runway to meet more citizens and also for citizens to have more time to engage them on what they plan to do if elected. But as a number of politicians – especially those of the Nigerian variety will tell you – it’s also a bad thing because it will make them spend more and leave them near exhaustion at the finish line.

But that’s not all. As far as electoral politics go, there’s no guarantee that longer time spent campaigning equals promises kept in the end. I have said it before that the only promises made by politicians are those they often do not intend to keep.

But Tim Marshall said it even more eloquently in his book, Divided: Why We’re Living In An Age Of Walls. “In politics”, he said, “the present is often more important than the future, especially when you want to be elected.”

Put squarely, campaign promises are made to be broken, with barely any leftover pieces for voters the morning after. Ask the British what happened the morning after Brexit. Yet, in our love of rituals, we hardly remember that campaign promises and manifestos are produced and packaged in gloss and rendered in poetry.

Since campaigns for Nigeria’s general elections officially began in September, we have seen candidates of the 18 political parties flitting across the country, holding rallies, attending town halls and debates and meeting different groups and communities.

Three of the presidential flag bearers – candidates of the All Progressives Congress (APC), Bola Ahmed Tinubu; Labour Party, Peter Obi; and the New Nigerian Peoples Party (NNPP), Rabiu Kwankwaso – have even gone beyond Nigeria, taking their campaigns to Britain’s Chatham House, a private political think tank.

Virtually all candidates contesting at national, state or local levels have been promising to turn our night into day and retrieve the paradise lost.

Well, if you have been living in Nigeria or have known it in the last eight years at least, this is what the promises look like: taming widespread banditry and kidnapping which have made major roads and highways in some parts of the country unsafe, with rail lines as the new targets; curbing inflation which is currently over 20 percent and unemployment at over 30 percent; reversing the new “japa” wave draining the country of some of its best professionals and young people; tackling systemic corruption; and fixing a political system which increasingly serves fewer and fewer people.

It’s a basketful. But politicians on the hustings all insist they have the magic wand. Does anyone really take them seriously? Do campaigns, manifestos and election promises affect electoral outcomes? An answer from a young member of the audience at a recent public lecture on campaign tracking hosted in Abuja by an online platform, NPO Reports, got me thinking.

Campaign manifestos are fancy election tools, but in the end, they are irrelevant to the electoral outcomes. The young man didn’t use these exact words but gave a parable from the odyssey of the first term of former Governor Kayode Fayemi of Ekiti State to illustrate his point.

Even though Fayemi kept faith, delivering significantly on his election promises, he lost to Ayo Fayose who ran against him when he contested for a consecutive second term. Fayemi was accused of “speaking grammar” and dispensing “big, big English”, in comparison to Fayose whose prioritised “stomach infrastructure”, euphemism for distributive politics and hanging out to eat roast plantain by the roadside.

In the end, it didn’t seem to matter what Fayemi’s election manifesto was or how far he actually went to keep it in his first term as governor. What mattered, it seemed, was that a perverse demand side (amply exploited by security agents working hand-in-gloves with vested interests) had yielded to the psychology of voter exploitation.

It’s not a peculiarly Nigerian thing. Whether it is Donald Trump, Boris Johnson or Jair Bolsonaro, we have seen political demagogues getting elected on what appears to be the most preposterous electoral promises, only for voters to bite their nails later.

But we have also seen those who meant well come to grief, when the tyre of political campaigns meets the road of governance. Ghanaian President, Nana Akufo-Addo, for example, made lofty promises before election, including creating a “Ghana-beyond-aid”. He was the poster-boy, not only of Ghana’s politics, but also of a continent that appeared bereft of role models.

But as a result of a combination of COVID-19 and the aftershocks, including wild swings in the commodity prices, Akufo-Addo is hanging by the skin of his teeth today, with the same voters who praised him to high heavens now pouring out onto the streets to demand his crucifixion. He is leaving Ghana worse off for aid and foreign loans!

Yet, that is not a reason not to track campaigns and manifestos. Since the MIT media laboratory developed the Promise Tracker in 2014, there has been an increasing use of tools to track politicians in many parts of the world. The evolution of these apps, hardly able to tame politicians’ shenanigans or even voter complicity, which I’m sure were present even from ancient Greece, has also raised interest in whether campaign documents should be justiciable or not.

That is, if APC candidate, Tinubu says he will rebuild our national security infrastructure, create jobs for youths and make Nigeria an exporting country; PDP flag bearer, Atiku Abubakar, is promising qualitative education, restructuring and prosperity; and LP candidate Obi is promising an industrial revolution and seven thematic areas of security; shouldn’t we be able to take them to court if any of them fails to keep their promises?

And why, in any case, are we so obsessed with the presidential candidates that we easily forget that candidates at the state and local council levels ought to come within the radar?

Asking politicians to legislate campaign manifesto is like proposing to prosecute the goat for the yam kept in its care. It’s never going to work. The good news though, is that as a result of improved demand on service delivery by citizens and other stakeholders, governments in a few states are making conscious efforts to create self-tracking mechanisms, which include monitoring and evaluation units.

It’s good to blame politicians for not keeping campaign promises and I think we should keep beating them over the head until they learn that it’s not just the rituals of campaigns and the poetry of campaigns that interest us.

But if politicians are ever going to take their promises seriously, then voters will have to do better on the demand side. Voters cannot accept to be paid off during campaigns and then turn around to complain that politicians are not keeping their promises after they have been elected. The payoff is the promise kept.

And it’s not only about the money. Perhaps if voters focus less on the drama and aso-ebi of campaigns and spend a bit more time to reflect on the “why” and, especially, “how”, of promises made, a lot of post-election misery can be avoided.

How many times have we heard politicians promise to deliver the moon on a stick only to say after elections that they never really knew that the predecessor made such a mess of things? And that excuse becomes the trope for another few years before the incompetence shows up for what it really is!

However well intended promises made, extenuating circumstances, like COVID-19, can upend even the best of intentions. Yet, even in such circumstances, there is always bandwidth for a turnaround. And we have seen, even from COVID-19 examples, that the choice of leaders that voters made was not only vital to recovery, but could also be an insurance against calamity.

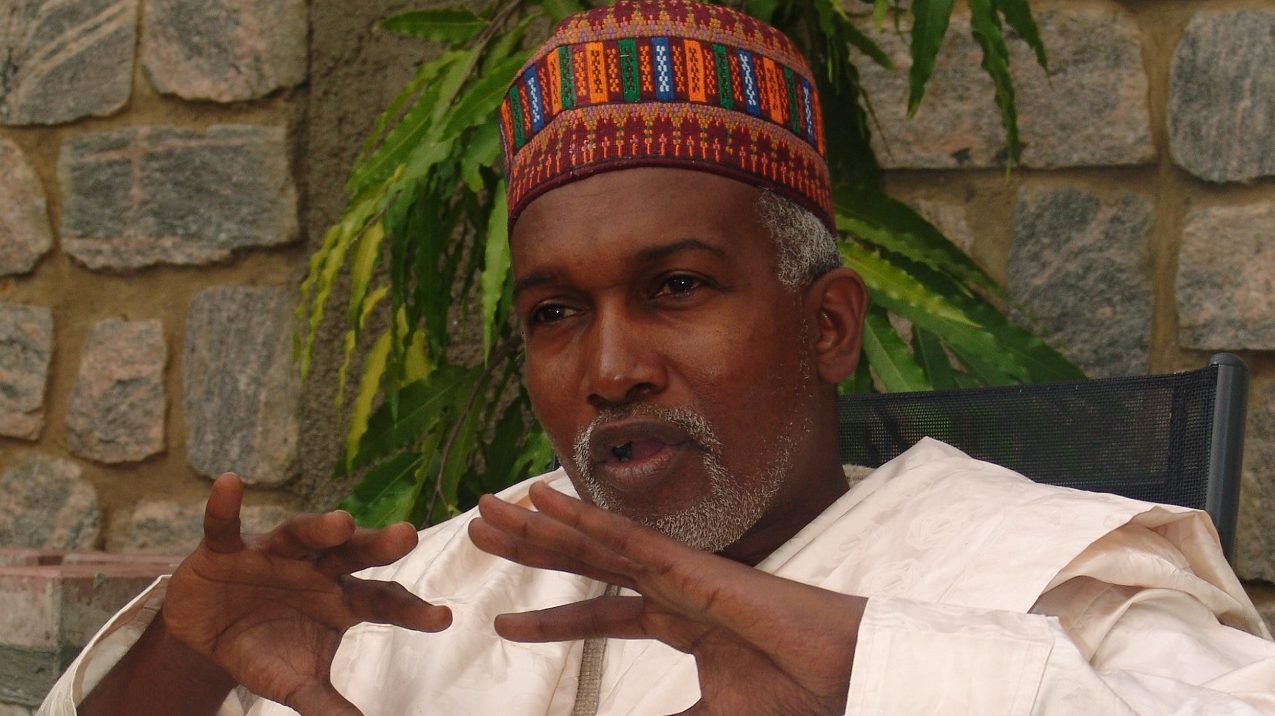

Ishiekwene is Editor-in-Chief LEADERSHIP