In the past couple of weeks so much has been said and reported, particularly in the new media about the so called resurgence of Boko Haram Insurgency and the progress or lack of progress in the efforts of the Armed Forces of Nigeria to deal with the crisis. A few of the reports and commentaries have recognized the nuances and ramifications of the insurgency and counter – insurgency, and have therefore offered holistic and balanced assessment of the situation. Others, unfortunately, have rendered largely sensationalized reports and simplistic commentaries on the crisis. These have seriously confused the situation and added little value to efforts at understanding the dimensions of the crisis or resolving it. However, the end of the 7th year of the Boko Haram Insurgency provides an opportunity to assess what has been achieved in the counter – insurgency efforts in the general sense, and the military line of operation in particular.

Before examining the efforts of the military in the North East, it is relevant to facilitate a deeper understanding of the Boko Haram phenomenon. At its outbreak, Boko Haram Insurgency represented what Combs describes as “a synthesis of war and theatre, a dramatization of the most proscribed kind of violence – that which is perpetrated on innocent victims – played before an audience in the hope of creating a mood of fear, for political purposes’’.

Also, apart from being religious fundamentalists, Boko Haram is a terrorist social movement. Like all social movements, it represents groups that are on the margins of society and state, and outside the boundaries of institutional power, Boko Haram seeks to change the system in fundamental ways, through a mix of incendiary rhetorics, unbridled criminality and unmitigated terror. The strategic end state of the insurgency is the establishment of an Islamic State in the Sahel covering parts of Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria, in the likeness of what ISIS envisioned for Iraq and Syria.

Without doubt, 2011 – 2014 was Boko Haram’s most active and successful years. During this period, the public lost confidence in the ability of the military to defend Nigeria’s territorial integrity. Media editorials and commentaries in both traditional and new media clearly indicated flow of public opinion. At a point, the 3 North Eastern States of Adamawa, Borno and Yobe were placed under a state of emergency. Some commentators even called for the removal of Service Chiefs. However, this order of events was not entirely strange.

Extant literature on the life cycle of terrorist organizations suggests that terrorist groups are most violent at the initial stages of their campaign. In this regard, Peter Phillips argues that “at the centre of the life cycle sits the grassroots support for the terrorist organisation. Competition for grassroots support shapes the timing and intensity of the terrorists’ competition with the government. The grassroots support that is captured during the early stages of conflict will eventually shape the life cycle of the terrorist organization”. Therefore, the behavior of Boko Haram leadership could be rationalized within this premise.

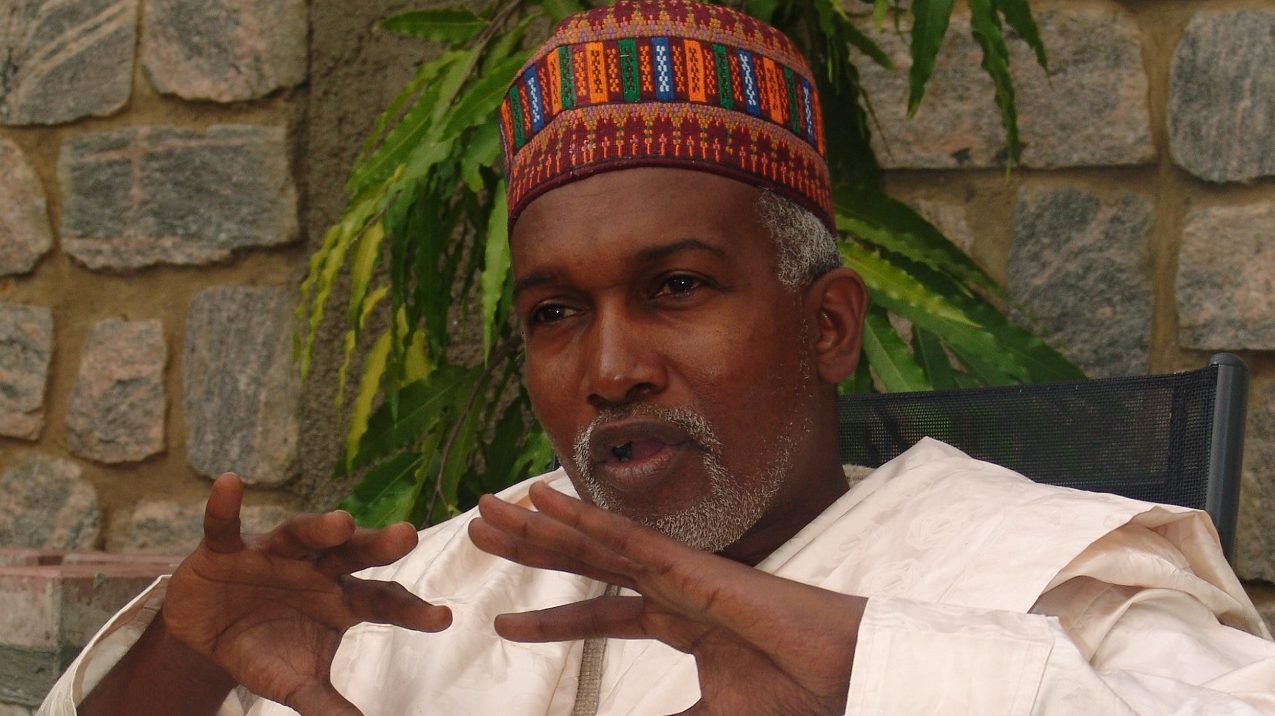

The emergence of a new government and leadership in the Nigerian Army in 2015 resulted in a new operational framework and design for the North East. The restructuring directed by the Chief of Army Staff, Lt Gen Tukur Yusuf Buratai brought about the creation of the Theatre Command and 8 Task Division, as well as Logistics and Forward Operational Bases.

Additionally, the concept of Mobile Strike Teams enhanced troop’s capacity to undertake fast strike operations to suppress Boko Haram Terrorists. These efforts have given traction to full spectrum and logistics supported kinetic operations across the North East Theatre. Similarly, reorganizations carried out by the Nigerian Navy and Nigerian Air Force helped to shape the battle space for effective joint operations. For instance, the Nigerian Navy established a Forward Operational Base in Fish Dam, Baga, while the Nigerian Air Force upgraded its formation in Maiduguri to the status of a division and established a Forward Operational Base in Munguno, among others.

Earlier efforts to analyse Boko Haram insurgency have been hampered by fixation on assessment metrics developed for conventional wars. These formulae are largely irrelevant to the situation at hand and accounts for the inaccurate and misleading conclusions regarding what has been noted as “ancient but new” type of warfare in the North East.

Therefore, in seeking to put forward a realistic assessment of Boko Haram Counter – Insurgency Operations, it is essential to reference the pioneering work of S Bjelajac developed during the Vietnam War, as the United States Department of Defence embarked on the measurement of its success or failure in the conflict. Though developed decades ago, the determinants remain valid and applicable to similar insurgencies, such as the Boko Haram Insurgency. Some of the factors include the following:

The latitude which a nation’s security forces enjoy in the conduct of military operations, Military Operations Other Than War (MOOTW) and civic duties within a contested territory (the 3 States of the North East is considered contested following Boko Haram’s declaration of a Caliphate) is a huge indicator of its firm standing during a counter – insurgency war. From a position where in 2015 troops were barely able to hold positions in Damaturu, Maiduguri and Yola, to a situation where troops currently hold and conduct offensive operations in border towns like; Mallam Fatori, Damasak, Baga, Bama, Gwosa, Chikun Gudu, among others, clearly shows that the Armed Forces of Nigeria have made considerable gains in its counter – insurgency operations against Boko Haram. It is also important to note that paramilitary organizations are also re-establishing their presence in these localities. The clear conclusion therefore is that Boko Haram and its ideology are in recession.

The Chinese military Strategist and Philosopher Sun Tsu noted, “If you know your enemy and know yourself you need not fear the results of a hundred battles”. This assertion highlights the primacy of intelligence in military operations, particularly counter – Insurgency. Consequently, the pattern of the flow of intelligence is an excellent determinant of progress in insurgency or counter – insurgency. Probably, the most significant general indicator of progress has to do with the source of intelligence. If the bulk of government intelligence is acquired as a result of volunteered support from the civilian population, it indicates strong support for the government and declining support for insurgents. The successes achieved by security forces in the North East, vis a vis the unrealised dream of an Islamic Caliphate are indicative of the direction of the pendulum. It is important to note that the critical issue is not the validity of the intelligence, but the voluntariness of the members of the public in providing information.

The main objective in an insurgency or counter – insurgency war is legitimacy and allegiance of the people. Popularity and support, and not geographical areas under control are the ultimate measures of success. As it stands, public opinion, both local and international are overwhelmingly in favour of government. This again shows Boko Haram in serious deficit. Inspite of healthy indicators and the general direction of the Counter – Insurgency Operations, skepticism abound. Analysts and commentators have pointed to the “slow pace” of execution of victim support programmes and reconstruction of the war ravaged communities in the North East as evidence of the lack of progress. It is therefore suggested that authorities at the relevant strata of government could look into these observations to leverage community participation in the continuing reconstruction and rehabilitation efforts.

The exercise of political authority and control in a contested area is also a key determinant of who has won the war, the insurgent (Boko Haram) or counter – insurgent (Government). Across the 3 States of the North East where Boko Haram had declared its caliphate, there is none where the terrorist group has political control or administrative machinery in place. Currently, the legitimate authorities in the 3 States determine and make political decisions across the strata of political authority. From all observable criteria, Boko Haram has no political influence whatsoever.

Certain legal indicators also point to who is in charge and in control in contested areas. For instances, it would be relevant to ponder on the following issues; How effective is government detection and prosecution of crime in the North East? Are laws being enforced? Is law enforcement being supported by the civil population? Is Boko Haram successful in their efforts to impose their own shadow laws on the population? The answers to these questions and their implications for the North East are obvious and do not call for any debate.

Another critical factor in determining which side has clearly established and imposed its authority is control of transportation and communication. For instance, the degree to which government feels free to transport its goods and services in unarmed or less armed convoys is a clear indication of firm government control. Also, the degree to which government has possession or guarantees the operability of telecommunication infrastructure is an indicator of its strength. In this regard, it is relevant to note that major arterial road networks within the North East which were hitherto closed for safety reasons have reopened and are currently being used daily. The fact that occasional attacks have been reported on some routes cannot invalidate the fact that other routes still remain safe. Also, communication has been restored to most areas within the states.

Contrary to the widely held belief, acts of terrorism such as the suicide bombings being experienced in the outskirts of Maiduguri of late do not represent an escalation, but a sign of weakness on the part of Boko Haram. At this stage in Boko Haram’s Insurgency, such actions serve primarily to compensate (psychologically) their sponsors and sympathizers within the population for the failures and lack of progress in other areas. Therefore, the recent resort to suicide bombings is basically an indication of Boko Haram’s frustration, declining influence and loss of confidence in its ability to achieve its strategic objective.

On the whole, Insurgency and Counter – Insurgency Operations are complex conflict situations. Deliberate and painstaking efforts are therefore required, if one must observe the nuances, subtle and swift changes that occur in such conflict environments. Drawing from the foregoing, the national strategic narrative that Boko Haram terrorists have indeed been defeated is unimpeachable. It is established.

The factors discussed above are very clear indicators. However, the successes achieved by the Armed Forces of Nigeria in the North East and their multiplier effects in other sectors do not summarily mean the end of Boko Haram Insurgency. It should be understood that the issue is also ideological. Therefore, credible threats still abound. Consequently, there are still imperatives for continuous investment in the Armed Forces of Nigeria, particularly in the areas of Training, Intelligence gathering, Aerial surveillance systems and Platforms. The time to do this is now. As we say in the military; a soldier who sweats in peace time, bleeds less in time of war.

Colonel Timothy Antigha is the Deputy Director Public Relations, 8 Division Nigerian Army