For a period of about five days towards the end of the month of October, Nigerian security forces were involved in clashes with members of the Islamic Movement of Nigeria (IMN). The Nigerian army later emerged as the principal antagonists in media reports of the series of clashes that began with a face-off between the group and some soldiers in the Zuba area of Abuja on October 27.

IMN claimed that the soldiers had threatened a peaceful procession of the group before opening fire on its members, in a bid to break up the procession. The army on the other hand claimed that its men were on a mission transporting ammunition to a military base in Kaduna, when they were attacked by the group in Zuba, forcing them to use live rounds to protect their cargo.

Unsurprisingly, the soldiers were heavily criticized after the deaths recorded in that first incident. Those deaths later led to further clashes, days after, near the Nyanya axis of Abuja, where even more deaths may have occurred, and in the Wuse 2 area, right in the city center. The major criticism against the army has been for opening fire on protesters who were “only” hurling rocks at its men, instead of seeking other less lethal methods of dispersing the crowd or maintaining orderliness in each of these cases.

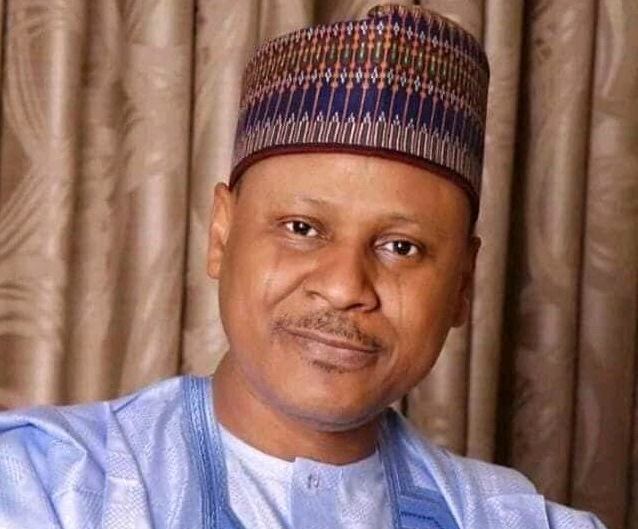

In judging how blame should be apportioned in the series of clashes, there is need to refer to history, beginning with the history of the soldiers and members of the majorly Shiite IMN. The head of the group is Sheikh El-Zakzaky, a popular Shia cleric, who is currently being held by the Department for State Security, DSS. He was arrested during the bloody aftermath of the alleged obstruction by the IMN of a convoy transporting the head of the army, General Tukur Buratai in 2015. In that episode, it is alleged (and since upheld by a judicial panel) that the army killed over 300 members of the group, who were later buried in mass graves. El-Zakzaky has also not been released, despite various court orders directing his release from custody.

It is rumoured that resentment against the group may have continued to brew in the army after the defiant act against the army chief, while the members of the group have continued to harbour a deep dislike for the military, for the death of its members and the continued detention of El-Zakzaky. The IMN have held numerous protests in the past demanding the release of their leader, some of which have led to heavy crackdowns by security forces. In short, the relationship between the group and security forces in general has been one of very high tension, and those clashes at the end of October are symptomatic of deeper issues that could spiral out of control if left unresolved.

As always, history is the best guide in the emerging tale of the Shiites’ ordeal. Many years ago, in Maiduguri, an Islamic scholar under the tutelage of Sheikh Mahmood Ja’afar, a popular Salafist Islamic cleric, broke away from Ja’afar’s spiritual guidance as he developed ideologies that ran contrary to that of his teacher. He garnered some following with his eloquence and later held a public debate against his former teacher, who held more conservative opinions about the spread of sharia. Sheikh Ja’afar was shot dead in a mosque a year after that debate, and some other clerics and others lost their lives in similar manner.

That scholar was Mohammed Yusuf, widely believed to be the founder of the Boko Haram sect. Members of Yusuf’s sect had gradually renounced the influence of all secular authority in their affairs, with rumoured backing of elements in the Borno state government. They had carried on independently and in defiance of all regulations outside their strict sharia code long before the government clamped down on the sect in 2009, killing Yusuf in the process. Today, events in Maiduguri and the northeast generally still tell the tale of that error in government judgment.

El-Zakzakky is thought to have developed ideologies modeled after Shiite principles that led to the Iranian Islamic revolution in 1979. He maintains close ties to Iran that, some fear, may go beyond mere scholarly enthusiasm. Notably, in its drive to export revolutionary thinking against secular authority outside its borders, Iran is said to have introduced Hezbollah into Lebanon, a move which has altered the politics of Lebanon permanently. Given this background and El-Zakzaky’s public rants against the establishment, it is fairly understandable that the government may be jittery about the IMN.

In the past, people resident in Kaduna have reported on the hostile nature of the IMN members to any interference during their processions and gatherings, often carried out in public places. With the IMN under El-Zakzakky already showing signs of disregard for constituted authority, some were not surprised about their altercation with the army in 2015. The reaction of the army to that event was highly heavy handed and deserves the condemnation it has generated, but the old issues surrounding El-Zakzaky and his followers have not gone away because of the lack of restraint by the army then, and they are still present after October.

It seems that El-Zakzaky had been on the radar of the security services before that unfortunate altercation with the army in 2015 provided the perfect opportunity to bring him in. The security fears that El-Zakzaky’s IMN appears to pose may have given the security services the confidence to continue to hold El-Zakzaky even after court orders for his release have been issued. It brings back the old debate about the interplay of the law with issues of national security. The president has been criticized for suggesting that national security exigencies take precedence over the rule of law. The truth is that this is a delicate matter that requires a delicate solution.

The killing of members of the IMN in October and at every other time certainly is not delicate. The storming of security barricades and use of Molotov cocktails by protesting IMN members is equally indelicate. Hurling rocks at military men carrying live ammunition and unprepared for anti-riot missions is also not respectful of the lives of those men, who were only doing their jobs, or the lives of others going about their innocent activities who may have been killed or injured during those clashes.

Just as the security forces and the protesting IMN members seem to be at an impasse about how best to proceed, Nigerians have been finely divided in their reactions to the series of clashes involving security forces and the IMN. That is just what overt state action leads to – division of people and radicalization of otherwise moderates. It is not inconceivable for there to be protesters who may have become hostile because a family member was part of the first 300 killed in Kaduna.

Religious division has caused Nigeria dearly in all its years of existence, especially in the recent past, and we are still reeling from the consequences of ill-conceived government action along those lines. As has been noted by domestic and international analysts, Nigeria cannot afford another insurgency of any form, and that is why it is so crucial for the government and security forces to get it right this time. El-Zakzakky needs to get his day in court and this cannot happen if the government continues to disregard the authority of the courts. Neglecting the courts is tantamount to summary, extra-judicial judgment and punishment.

If IMN’s ideologies under El-Zakzaky pose a threat to national security, only through the outlining of facts leading to such conclusion in a judicial setting can get the people behind the government. Otherwise, the continued life-threatening irresponsibility of the security forces and the IMN protesters will lead to deep divisions that may finally be exploited by selfish foreign interests for their own gain. The government, and Nigerians as a whole, must be mindful of the lessons of history and adopt measured response to this delicate matter.

For comments, send SMS (only) to 08058354382