Saudi Arabia has agreed to give up control of Belgium’s largest mosque in a sign that it is trying to shed its reputation as a global exporter of an ultra-conservative brand of Islam.

Belgium leased the Grand Mosque to Riyadh in 1969, giving Saudi-backed imams access to a growing Muslim immigrant community in return for cheaper oil for its industry.

It now wants to cut Riyadh’s links with the mosque, near the European Union’s headquarters in Brussels, over concerns that what it preaches breeds radicalism.

The mosque’s leaders deny it espouses violence, but European governments have grown more wary since Islamist attacks that were planned in Brussels killed 130 people in Paris in 2015 and 32 in the Belgian capital in 2016.

Belgium’s willingness to put its demands to oil-producing Saudi Arabia, a major investor and arms client, breaks with what EU diplomats describe as the reluctance of governments across Europe to risk disrupting commercial and security ties.

Riyadh’s quick acceptance indicates a new readiness by the kingdom to promote a more moderate form of Islam,

one of the more ambitious promises made by Crown Prince Mohammed Salman under plans to transform Saudi Arabia and reduce its reliance on oil.

The agreement in January, coincides with a new Saudi initiative, not publicly announced but described to Reuters by Western officials, to end support for mosques and religious schools abroad blamed for spreading radical ideas.

The move towards religious moderation, and away from the extreme interpretation of Islam’s Salafi branch that is espoused by modern jihadist groups, risks provoking a backlash at home and could leave a void that fundamentalists try to fill.

Saudi Arabia’s recent moves on religion are seen by Belgian diplomat Dirk Achten, who headed a government delegation to Riyadh in November, as a “window of opportunity”.

“The Saudis are disposed to dialogue without taboos,” he told Belgium’s parliament last month after the mission was hastily put together after the assembly urged the government to break Saudi Arabia’s 99-year, rent-free lease of the mosque.

He also cautioned: “Some do not, or barely, admit that this form of Salafism leads to jihadism.”

Details of the mosque’s handover are still being negotiated but will be announced this month, Belgian Interior Minister Jan Jambon told Reuters.

The diplomatic contacts, led by the countries’ foreign ministers, were intended by Belgium to prevent what Jambon called an “exaggerated response” from Saudi Arabia — indicating the Belgian government had sought to ensure there was no diplomatic backlash.

This, he said, was “under control” following a visit to Belgium last month by Saudi Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir.

Before Saudi Arabia took control in the late 1960s, the Grand Mosque was a disused relic of the Great Exhibition of 1880, an Oriental Pavilion.

Saudi money converted it to cater to migrants from Morocco invited to work in the country’s coal mines and factories. It is run by the Mecca-based Muslim World League (MWL), a missionary society mainly funded by Saudi Arabia.

Concerns about the mosque grew as militant groups such as Islamic State started recruiting among the grandchildren of those migrants, many of whom say they still feel they do not belong in Belgian society, opinion polls show.

Belgium has sent more foreign fighters to Syria per capita than any other European country.

Belgian officials now suggest the Muslim Executive of Belgium, a group seen as close to Moroccan officialdom, should run the Grand Mosque.

Although the Saudi government has denied any role in the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks against the U.S. which killed more than 3,000 people.

Authorities added that 15 of the 19 airplane hijackers who carried them out were from Saudi Arabia and linked to late Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, the plot’s Saudi-born mastermind.

Bin Laden was a follower of Wahhabism, the original strain of Salafism which has often been criticised as the ideology of radical Islamists worldwide.

Yet many of Islamic State’s positions are far more radical than Wahhabism, the ultra-conservative branch of Islam dominant in Saudi Arabia and founded by 18th century cleric Mohammed ibn Abd al-Wahhab.

A classified report by Belgian security agency OCAD/OCAM in 2016 said the Wahhabi branch of Islam promoted at the mosque led Muslim youth to more radical ideas, sources with access to the report said.

“The mosque has influence to spread this hateful ‘software’,” a senior Belgian security source said. “Nobody paid attention for decades.”

Belgium’s parliament said what it preached was “a gateway or even a predisposition to a more combative Islam that is violent”, calling in October for an end to the Saudi lease.

Slideshow (8 Images)

The same month, immigration minister Theo Francken tried to expel the Grand Mosque’s Egyptian imam of 13 years, calling him “dangerous”, but a judge reversed that decision.

Belgian security sources say there is no proof imams at the Grand Mosque preached violence or have had links to attacks.

Some who went to fight in Syria had studied there but men are more prey to recruiters for militant groups online and on the streets of underprivileged boroughs such as Molenbeek, in Brussels, where some of the Paris attackers lived, they say.

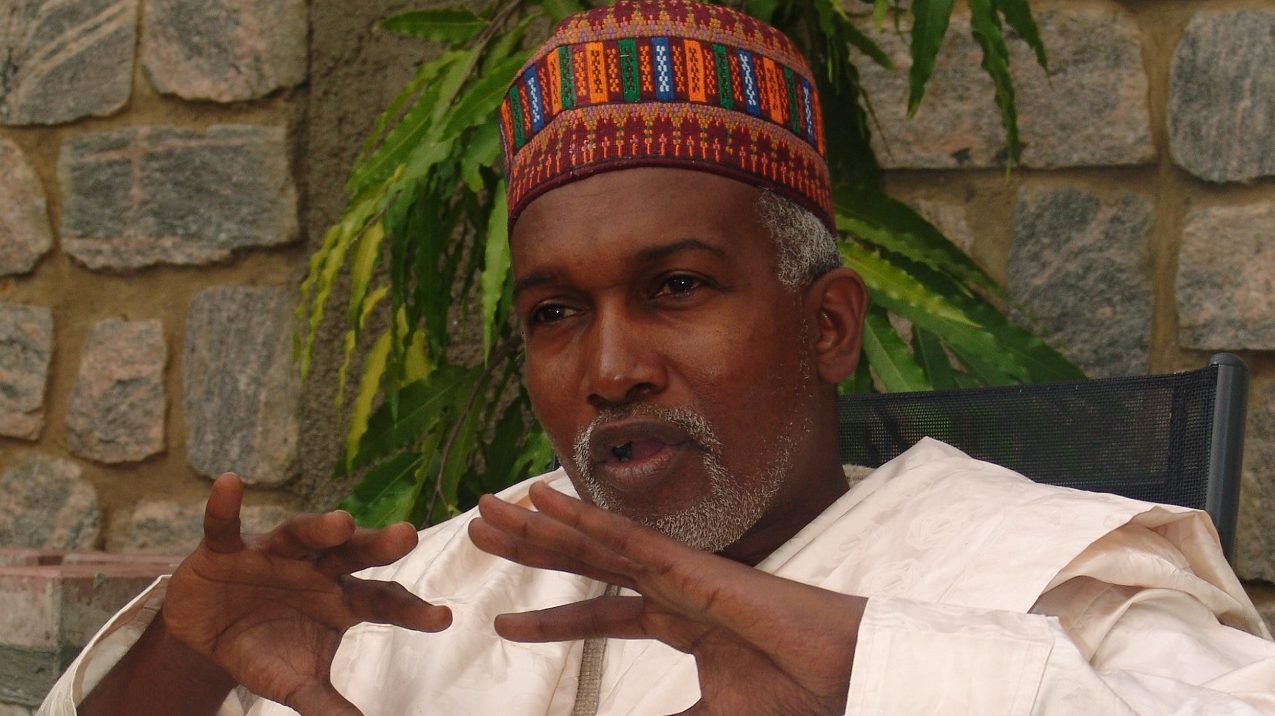

Tamer Abou El Saod, who was appointed director of the Grand Mosque in May, says there are problems over the way it is perceived but denies it espouses a fundamentalist version of Islam.

He says he is ready to work with Belgian officials.

“There are changes happening already and there are even more changes coming in the very near future,” he told Reuters.

Belgian leaders say they want the mosque to preach a “European Islam” better aligned with their values – a familiar refrain across Europe following the Islamic State attacks of the last few years.

For Saudi Arabia, the mosque is a chance to prove it is turning over a new leaf after years of accusations it turned a blind eye to, if not actively endorsed, extremist ideology.

Crown Prince Mohammed has already taken some steps to loosen ultra-strict social restrictions, scaling back the role of religious morality police, permitting public concerts and announcing plans to allow women to drive this summer.

The changes, however, may be too late since most militant groups that emerged at some point from Saudi networks have grown independent, says Stephane Lacroix, a scholar of Islam in Saudi Arabia.

“That this is going to solve the problem of radical Islam because if the Saudis change, everything’s going to change: It’s not the case,” he told Reuters. (Reuters/NAN)