One of the first things I picked up very early in this business of public affairs analysis is something senior colleagues referred to as Afghanistanism. If you were told a column, story or essay, you had submitted for publication reeked of Afghanistanism, it was clearly a subtle kind of condemnation. It meant dabbling into a remote subject that was not of immediate consequence whereas you could have chosen a better topic of greater local value and relevance. In other words, the phrase “Afghanistanism”, was not a compliment. It was a label for absent-mindedness, an obsession with far-away places and events, sounding eloquent about other people’s issues while overlooking the same problems at one’s doorstep. Afghanistanism was thus projected as a perfect exemplification of parachute journalism. But here we are, at this time, in the past two weeks, and in the past few days, Afghanistanism is now suddenly no longer a flight of fancy. It has become the symbol and the very definition of much that is wrong with our world. It is the news of the moment, not so distant anymore, but a source of worry for the entire world. I guess it is now possible to indulge in Afghanistanism without being accused of an idle journey to distant places.

Over the weekend, Afghanistan imploded. Its President, Ashraf Ghani abandoned the Presidential Palace and fled towards the direction of Tajikistan. The Vice President went in another direction. Security agents including the police and the military dropped their weapons and fled too. Ordinary citizens headed towards every available border to become refugees in neighbouring countries. The United States which had been involved in the politics of Afghanistan since 1999 is also on the run out of the country, as it shuts down its embassy in Kabul, burning down sensitive documents, and rushing to airlift its citizens out of Afghanistan. The British, and NATO soldiers who had both supported the US in Afghanistan, are also on the run. It is an unfolding chaos and tragedy, the exact end of which no one knows, and that is precisely what makes all of this a sad day for the rest of the world. The fate of the people of Afghanistan hangs in the balance. Their future is uncertain. Their government has collapsed. A bunch of radical extremists, terrorists, ideologues and tribal warlords, known as the Taliban, are now in charge. They have taken over the Presidential palace and the entire country. In the 1990s, they were in charge of the country. The people of Afghanistan have just been taken back to the 20th Century. That country has turned full cycle to the age of fundamentalism, the oppression of women, disdain for education and abuse of human rights. Tragic.

The crisis in Afghanistan speaks to the failure of American diplomacy and specifically of US foreign policy. Diplomatic relations between the United States and Afghanistan dates back to 1935. In the course of that relationship, the United States was responsible for setting up in that axis, a bunch of extremists known as the Mujahideen as part of the Cold War with the Soviet Union and China, two countries with which Afghanistan shares borders. The Mujahideen would later become the Taliban. They gained control of Afghanistan. If America thought it was exporting its Western style democracy to Afghanistan, a majorly Muslim country with strong ethnic cleavages, and that the people would adopt American ideology, it was grossly mistaken. The Muslims of Afghanistan were not willing to abandon their religious and ideological beliefs, and many resented the Western way of life. It did not take long before Afghanistan became the home of religious fanaticism and the headquarters of the Al Qaeda. Matters later took a turn for the worse when the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1267 which created the al-Qaeda and Taliban Sanctions Committee, and the classification of both groups as terrorist groups with sanctions over their funding, travel and activities.

Osama Bin Laden in the face of this rose to the top. In 2001, Ahmad Massoud, commander of the Northern Alliance, an anti-Taliban coalition was assassinated by the al-Qaeda, which by then had grown in strength and scope. As it happened, later, on September 9, 2001, terrorists struck in the United States, in the tragedy now known as 9/11. The US and its allies promptly launched a retaliatory offensive: Operation Enduring Freedom, and later, Operation Freedom’s Sentinel against the Al-Qaeda. The Taliban and its totalitarian government fell in the face of this offensive and hence resorted to a guerrilla warfare against the West and the government installed by the US in Afghanistan. Over 2, 400 US soldiers have died in the war against the Taliban. Over 20, 000 were wounded. Washington has spent over a trillion dollars. The British have also lost over 450 soldiers to the battle. But even with the negotiations over the years, and America’s training of Afghan soldiers to keep the Taliban at bay, the intervention in Afghanistan by the US and NATO has proved futile and unwinnable. With the return of the Taliban to Kabul, the war against terror in Afghanistan has proven to be a colossal failure. America has been humiliated. What we are witnessing is two decades of bad judgment and miscalculations. In July, President Joe Biden boasted that Kabul would not fall and the day would not come when the Taliban will overrun the country. It took the Taliban just ten days to overrun the entire country. America and its allies were overwhelmed. The now deposed Afghan government and the US have been trading blames. But after the initial denial that this is not another Saigon in South Vietnam, 1975, it is interesting to see American diplomats eating their own words. Anthony Blinken, the US Secretary of State, and other Washington policy wonks, have now come to the realisation that this is a failed mission for the United States as was similarly the case in Vietnam, Sudan, Somalia, Yemen, Sudan, Iraq, and Libya.

America did not need to stay in Afghanistan forever. It is simple and direct logic that the Afghans would have to clean up their own mess, at some point, but the leaders of Afghanistan failed to govern properly, and America’s hasty withdrawal plan was a mistake. America misread the politics of Afghanistan. It underestimated the Taliban. It also overestimated the Afghan National Defence and Security Forces (ANDSF). The US spent loads of dollars training what became known as the Afghan Special Forces. It was thought that they had received enough training to be able to secure their own country against the terrorists. But that was pure fiction. The ANDSF lacked real capability. The Forces were mismanaged by the local authorities. When the Taliban launched an onslaught, the ghost army that the US and other nations thought they had set up took to its heels. The disaster that has now occurred was long in coming. It was a disaster foretold. In February 2020, the US struck an agreement with the Taliban in Doha. That has failed too, in part because even the Afghan leaders were excluded from it.

The regional warlords who both the US and the Afghan government thought would resist the Taliban did not raise a finger as The Taliban overran the provinces all the way to the Capital. The US thought Pakistan would help. Instead, Pakistan became a sanctuary for the Taliban. The US may well claim in the end that in 20 years it helped to reduce the scope of terror and the growth of terrorism in the world, but the failure in Afghanistan, spanning about four US administrations, looks ironically as a reinforcement of terrorism. The return of the Taliban is bound to embolden terrorist groups across the world. It will grant them confidence and hope that they can also achieve the same kind of triumph. Twenty years later, the US may have lost so much but it is the entire world that is at risk. The thinking that the US and its allies can save humanity, or that any country at all can rely on the omnipresence or the “indispensability” of the United States has been exposed as one of the biggest lies of the century. When it suits its purpose, the US will review its own priorities and it would not matter to the average American taxpayer whether you sink or float.

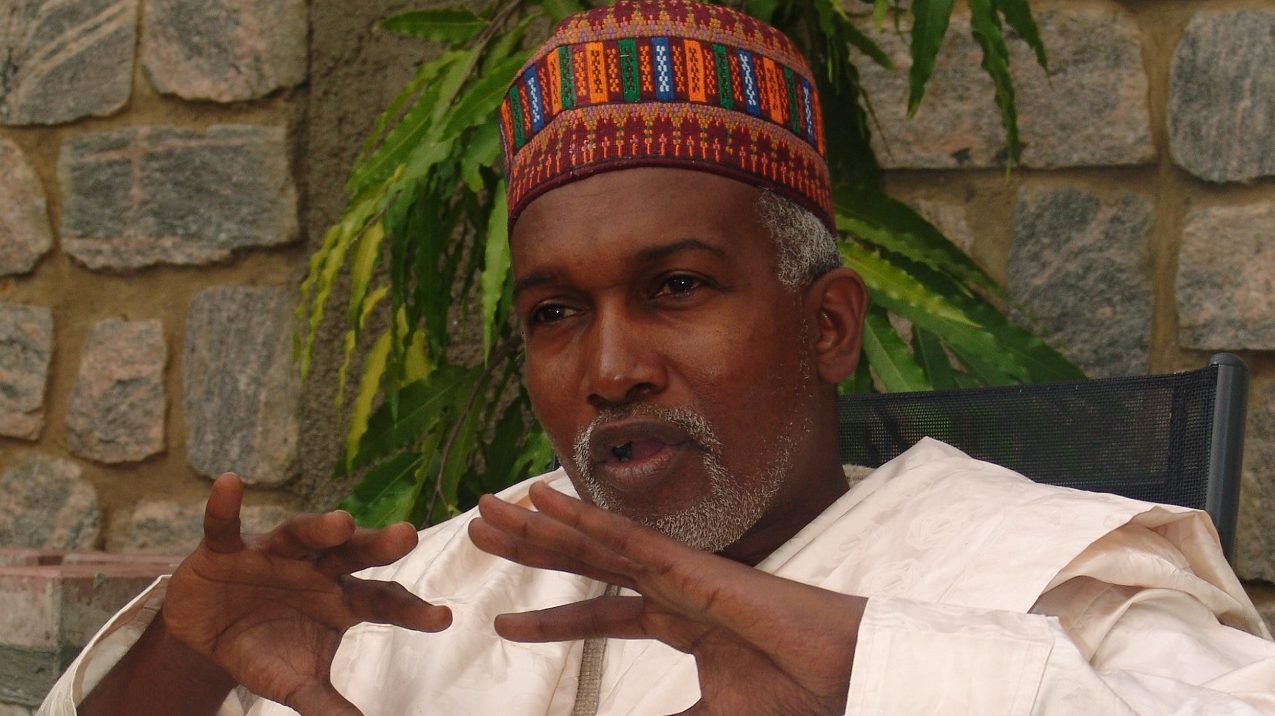

And it is at this point that the prompt intervention by Nigerian President, Muhammadu Buhari becomes relevant. In an article published in the Financial Times of London, the same day Kabul fell to the Taliban, Buhari placed his fingers rightly on the threat that the fall of Kabul poses to Africa. He referred to Africa as “the new frontline of global militancy” and called for global action to fight terrorism. He says: “We must not complacently assume that military means alone can defeat the terrorists. If Afghanistan has taught a lesson, it is that although sheer force can blunt terror, its removal can cause the threat to return.” Indeed, there are many lessons to learn from the Afghan debacle. He would go on subsequently to say that “a lack of hope is the chief recruiting sergeant for the continent’s new brand of terrorism.” This commentary was on point in every regard. I am tempted to suspect they just recruited someone with a sharp brain into the Nigerian Presidency. When the President returned from the UK, we were told he and his delegation would go into isolation in line with official regulations. And then from isolation, the President has just signed the Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB) into law. I digress. The big point about Afghanistan is the need to realise its implications for the global war against terror, US Foreign policy, and the balance of power in the world. Professor Bolaji Akinyemi on Arise TV, analysing the dilemma that the world faces spoke about the “clash of civilizations” (an apt reference to Samuel P. Huntington) and the likely emergence of “a new world order.” But is Africa prepared?

The failure of US policy in Afghanistan has occurred under the watch of President Joe Biden, even if it is an inherited crisis. Will it affect his rating? Is the average American bothered about whatever happens to the people of Afghanistan? What does the future portend for Afghanistan? The international community would probably make the usual noise about the need to protect human rights and refugees and the rule of law, and perhaps the UN Security Council would threaten to impose sanctions, but in the end, it is only the Afghans that can determine their own future. There is no way the Taliban can overrun Afghanistan, chase away a sitting government and seize power without the people’s tacit compliance. America must learn not to dictate ideological choices to others, in a diverse and complicated world.

II: Hichilema: Zambia Shall Be Free

As a secondary student, one of the compulsory literature texts that my set read for the West African School Certificate Examination (WASCE) was a book titled Zambia Shall Be Free by Kenneth Kaunda. Our teacher had a funny way of pronouncing Zambia. He would turn Zambia into “Zam-bi-u Shar-lll -Be Friii” by Kerr-nnerthi- Kar uuun dar”. Till today, some of my old classmates in that literature class still refer to Zambia as “Zam-bi-u”. Fond memories of those old days. Kenneth Kaunda, the author of that literature text, in which he documented the independence struggle in his country, died recently at 97. He was Zambia’s President from 1964 – 1991. There have been six Presidents in Zambia since 1964. The seventh was elected this past weekend, August 12, and it was the third time power has shifted peacefully from a ruling party to the opposition since independence. It is unfortunate that Zambia like other African countries gained flag independence from colonial rule, but the dream of concrete freedom articulated by Kaunda and other African leaders has not yet been realised. Zambia in particular has been unfortunate. Rich in copper but poor in leadership. I see the election that was concluded on August 12 as an attempt by Zambians to take back their country. They made a powerful statement about people power. They resolved that Zambians deserve to be free from the grips of corruption, nepotism, neo-colonialism and the forces of retrogression. The just-concluded parliamentary and presidential elections in Zambia offer an indication that the people’s voices and choice should matter most in a democratic process.

It was a referendum on President Edgar Lungu’s languid leadership. When Lungu succeeded Michael Sata in 2015, he promised to put an end to nepotism and inefficiency. He was hailed as a reformist but he ended up as a hypocrite. As recently as last month, when he went to London for a Global Education Summit, he had three members of his immediate family in his entourage and he shamelessly tried to defend himself. He even forced an amendment of the Constitution to allow him have a third term in office. He is leader of a Pentecostal Assembly with a Ph. D in Theology but he ran Zambia like the chief priest of a local cult. He readily boasts about the infrastructure that he has provided, but Lungu sold the soul of Zambia’s commodity sector to the Chinese. He incurred debts. The country went into recession. Ahead of the August 12 elections, he deployed the military to intimidate the opposition. He shut down the internet. He threatened to jail Hakainde Hichilema, Presidential candidate of the main opposition party, the United Party for National Development (UPND). In 2016, Hichilema lost the Presidential contest to Lungu by a mere 100, 000 votes.

Last week, and as announced yesterday by the Zambian Electoral Commission, this time around, Lungu lost to Hichilema, 1.8 million votes (39%) to 2.8 million votes (59%). The defeated incumbent President is now saying the election was not “free and fair” and that his supporters were intimidated. The same Lungu is condemning an election that he controlled by every means possible. Zambia has a registered voter population of 7 million out of a total population of 19 million citizens. Voter turn-out was 70% on election day, mostly youths who have now sent a strong and clear message that Lungu has overstayed his welcome. Hichilema, 59, has his job cut out for him: to ensure the freedom of Zambia from the forces of neo-colonialism, economic failure, nepotism, cronyism, incompetence, COVID-19, and elite stupidity. Above all, he must learn from the mistakes of Edgar Lungu.