Out of School Children as an Educational Menace: Towards a Policy Framework for Taming the Scourge in Nigeria

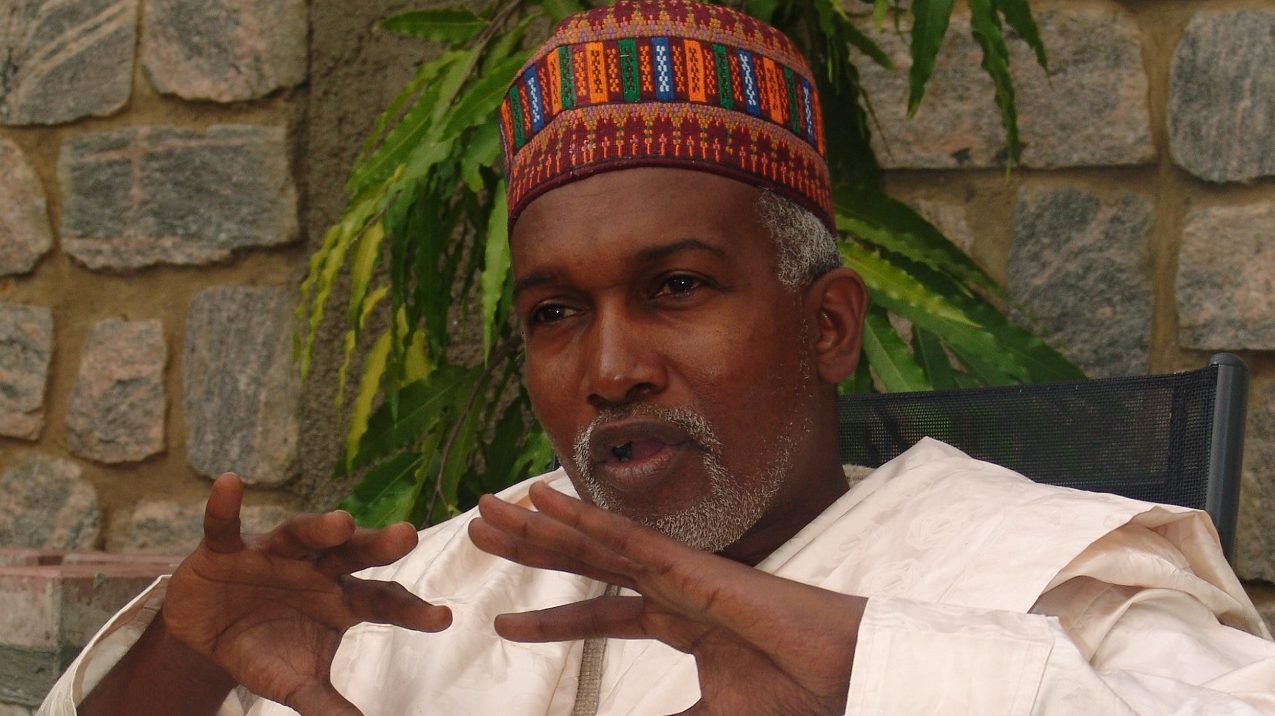

By Abdulrashid Garba, PhD; FCASSON; MNAE

Professor of Educational Guidance and Counselling

Department of Education, Bayero University, Kano

| Convocation Lecture Presented at the 6th Convocation Ceremony of Federal College of Education (Technical), Bichi, on Friday, July 16th, 2021, at the College Conference Hall |

1.0 Introduction

Education is undoubtedly critical to human development. Although there are questions such as ‘which education’, yet we still assume that conventional education which is largely in reference to type, quality and quantity paves the way for productive life. There is no doubt that education is the impetus for social and economic development, but yet it is the least in terms of receipt of parental and official attention. Few parents show any serious care and concern for education, and at the same time very few demonstrate any genuine concern about the education of their wards. Governments at all levels seem to demonstrate their concern for education only in annual budgetary allocations. Attention to education should not only be demonstrated through budgetary allocations alone, but through meaningful timely releases. Equally governments at all levels seem to be touching education on the surface by spending a large chunk of money on surface issues without digging deep into the real areas of needs. This inadequate official attention and seeming populist stance of government to education is what actually breeds discontent to education at all levels, and that is what constitutes the actual roots of many impending issues related to education such as out of school children.

Each time government or any other interested stakeholders intend to make some efforts towards ameliorating any of the problems in education; they often resort to seminars and conferences. The reasoning here is that seminars and conferences pave the way for articulating solutions. The reasoning may be acceptable but it is not far-fetched. Solutions to many of the problems in education are already within reach in form of laws and policies. In view of this perspective, his is this paper postulated three main assumptions have been identified and used as the main premise of this presentation. The first assumption is that if governments and all other stakeholders can be resolute in the implementation of those aspects of the extant laws and existing policies that concern them, most problems in educational delivery will fade away and out of school children will be brought to the barest minimum. The second assumption is that if government will be resolute in the provision of ‘ideal school’, where every child has equal opportunity to learn, most problems in education will naturally fade away and out of school children will be brought to the barest minimum. The third assumption is that if government will empower school neighborhood, Parents-Teachers’ Associations (PTA), Old Boys Associations and the traditional authorities, on one hand, and local law enforcement outfits (such as Hisbah Board) on the other, they can be of great use in the amelioration of out of school children.

It is against this background that this presentation looks at out of school children as an educational menace with an overall objective of evolving a handy tripartite policy framework for taming the scourge in Nigeria. To be able to do that effectively the paper begins with a discussion of the concept of and misconceptions about out of school children. The main causes of the problem have been categorized into five classes as follows: socio-cultural practices (SCP); economic circumstances (EC); practical relevance (PR); technicalities and bureaucracy (T&B); and security challenges (SC). Previous efforts by international organisations and municipal authorities at taming the tide of out of school children have been reviewed. For the evolvement of a tripartite policy framework for addressing the menace in Nigeria, the assumptions underpinning this presentation as highlighted earlier, have been used as a spring board. That means, the three assumptions have been used to frame the three divergent premises: extant laws and existing policies; an ideal school; and empowerment of some select stakeholders, for policy formulation. The paper concludes with some additional recommendations on inter- and intra-governmental synergy and cooperation for purposes of taming the scourge of out of school children in Nigeria.

2.0 Understanding the Concept of and Misconceptions About Out of School Children

The term out of school children is usually in reference to all dropouts and all other children that have never been to formal school. This is just a part of the definition as it only partially describes the phenomenon. The other part is often ignored – and that is out of school children are not necessarily to be found outside the school system only. Out of school children are also inherently present within the four walls of what we call schools. Just for a child to wear uniform and remain in school is not enough to be considered a school-attending pupil. The purpose of being in school is to obtain some levels of education and skills as enshrined in the National Policy on Education (2014). That means if a child goes to school and for some reasons (good or bad) could not get the required education and training, that child is surely as good as out of school. If a school is not secured, or has no reasonably furnished classrooms, or the basic structural and infrastructural facilities are not provided, or there are no qualified teachers, or the necessary teaching/learning materials are not readily available, and so on, that child is just an ‘official out of school child’.

Discussions on out of school children are usually supported with figures, numbers and estimates. To obtain these figures, numbers and estimates Nigeria usually relies more or less on data from UNESCO and UNICEF. Although the phenomenon of out of school children is undoubtedly real, the figures are sometimes accorded prominence over and above other more important considerations, such as real root causes of the problem and possible locations of solutions. I repeat, the problem of out of school children is real. This does not in any way mean that the figures – usually by region, by country, by States and by gender – cannot be questioned. Estimates and figures are good for especially planning, but of fundamental importance is understanding the root cause of the problem. Understanding a problem is more than half way to solution.

In many cases, where both household survey and administrative data are available, the estimates of out of school rates differ. The magnitude of the discrepancy may be substantial, which affects our perception of the school exclusion problem at the most basic level. These differences may stem from conceptual differences between enrollment and attendance, the definition of the target population, and the definition of “in school.” In some cases, it appears that some of those who are officially counted as out of school are actually enrolled in preschool or unregistered non-formal education programmes. In some instances children enrolled in non-formal schools are considered as out of school, (Combs, 2011).

These are all pointers to the fact that figures and estimates on out of school children should ideally serve not as the ultimate, but as a stepping stone towards action plans for establishing valid and reliable national figures.

3.0 The New Normal and the Escalation of Out of School Children

The outbreak of COVID-19 had some far-reaching consequences on education in especially Nigeria. Most industries, including education, have been brought to a standstill as a result of efforts to curb the spread of the virus. The question of the future of education has become more pertinent as millions of children across the country stayed at home during the escalating period of the pandemic. The fact is that the COVID 19 protocols which greeted the arrival of the pandemic were as challenging as the school closure. Both the COVID 19 protocols and the closure of schools have in no small measure escalated the problem of the out of school children,. The post-COVID-19 era brought forward a new normal. New normal was to accelerate digital transformation. These include for example, digital economy, digital government and digital education. Within the new normal, the situation presents a unique challenge to the educational sector and the decision-making process. Is digital education possible in Nigeria? This so-called new-normal in education, in other words means e-learning and children’s’ radio education programmes. But the question is: where is the power? We should not expect parents who cannot afford to pay for the child’s transport to school to bear the costs of android/computer; costs of internet data; costs of transistors and accessories; and so on. If Nigeria or any Sub-Saharan country is contemplating digital education in this present economic and environmental reality is only toying with extinction.

4.0 Out of School Children: Root Causes of the Problem

At different times different governments introduced different economic adjustment measures such as increase in prices, especially of oil and related products. Even with supposed futuristic economic benefits, many of such measures have far reaching negative implications on people and families. At the macro level the government had to take such economic measures to be able to improve or at least maintain infrastructure, including that of education. At the micro level the implications of government economic policies is making the means of sending children to school a big problem to parents. Whatever happens there will be implications to education. If government does not maintain infrastructure especially in schools and the educational sector in general, the dream of an ideal school where every child will hope to be will be shattered. If parents, on the other hand, are pushed more to poverty and a situation of want, it becomes difficult to send children to school. Such children will ultimately drop out of school, or may never be enrolled or may become ‘official out of school children’. At the roots of the problem of out of school children are five broad groups of causes. These are: socio-cultural practices (SCP); economic circumstances (EC); practical relevance (PR); technicalities and Bureaucracy (T&B); and security issues (SI).

4.1 Socio-cultural Practices (SCP)

Socio-cultural barriers inimical to children’s education include prioritizing market and or business over schooling; prioritizing one gender over the other, (males over females in some areas, and the vice versa in some others): prioritizing urban areas over rural areas; and so on. Examples of cultural barriers inimical to children’s education are the issue of marriage at tender ages and total abhorrence to ‘western education’. There are some other practices which some cultures deem necessary for every child before enrolling into in school. Such practices include training in the house chores and in the family businesses, attending and obtaining Qur’anic education, and so on. This ultimately leads to failure to get children enrolled in school at the appropriate age. There are again some other practices in schools such as dressing norm and style for example, which the society deems incompatible with our belief system.

Social and cultural causes of out of school children are often over-bloated, not many of them are in any way out of hand. They constitute a problem largely because parents and other social institutions are having their ways unchecked, on one hand. On the other hand, successive governments decided to be more or less an onlooker with little or no efforts at checking the excesses of some parents and other social institutions pertaining to children’s education.

4.2 Economic Circumstances (EC)

Government’s economic adjustment policies, for example, do not seem to favour parents; as a result, sending their children to school and paying for their education (and other supporting expenses) become a huge problem. There is also an issue of cost burden on parents: cost of going to school on daily basis; cost of uniform and other school related dresses; cost of feeding (especially lunch); cost of books and other academic materials. All these have far reaching implications on sending children to school. Other economic circumstance inimical to sending children to school is that parents believe that children are more useful to them at home and in the farm than in school. In many instances children have to engage in some economic activities in order to feed themselves and perhaps to finance their education by themselves.

Economic circumstances of parents which seemingly make it difficult for them to bear the costs of the education of their wards should not have been any cause for concern, simply because extant laws and existing policies have provided for free education. That is the parents should not have been allowed to bear many aspects of the costs of children’s education. The only problem is perhaps, that either governments are not keen on the implementation of the provisions of laws and policies on free education, or the implementation has not been forthright.

4.3 Practical Relevance (PR)

British educational policies did not seem to have met the local peculiarities and aspirations of Nigeria. That actually necessitated the need for a truly Nigerian educational policy. The current national policy on education (1977 to 2014) is the first indigenous educational policy. This part of the history is what perhaps pushed parents to continue to question the practical relevance of education to the welfare and wellbeing of their children. In situations where some people have ‘made it’ in life without even basic education, misinformed section of the society are likely to look down upon education, and are less likely to enroll their children in school. The general erroneous opinion is that the curriculum does not seem to reflect practical realities of immediate and local communities. Parents often compare schooling to other supposedly ‘more beneficial’ ventures. Parents would rather engage their wards in some ‘more beneficial’ economic activities because no one can be guaranteed a job after schooling. The often funny stance of many parents is that education is no more a means of social mobility.

The question of relevance in education has once been a topical issue of some concerns, but now the debate is over and outdated. Almost on annual basis the Nigeria Educational Research and Development Council (NERDC) has been in the practice of review of instructional materials whose purpose was, among others, to address the issue of relevance. The National Policy on Education has undergone several reviews, at least five times since 1977. I believe the reviews will continue depending on time and needs. The purposes of those revisions were to, among other things; address the issue of relevance of education for the achievement of overall national objectives.

4.4 Technicalities and Bureaucracy (T&B)

There are certain issues that are more or less technical which compound the problem of out of school children. Technicality here is in reference to processes, activities and detailed method of educational delivery. If today, for example, all out of school children in any of the States will present themselves to the government with a request to be enrolled in schools – that will be the beginning of yet another embarrassing moment. There are practically no schools available to accommodate them. From within the available schools the classrooms are not in a position to attract and retain the children. Virtually many of the essential facilities are either not in place or out of order. This is one of the major causes of out of school phenomenon. Teachers are either not available or are less qualified. Where there are qualified teachers their morale is so law so much that they are incapable of using their knowledge and experience to attract children to school. Schools lack facilities to accommodate diverse nature of children’s population. Bureaucracy in this context is in reference to a body of administrative policy-making group in education, usually characterized by special functions. Every year there is usually an impressive budgetary allocation to education, with little or no supportive action. The bureaucracy in education prefers ‘votes earning’ projects over and above realistic high impact education projects. Education is often over-politicized as free education remains a mere slogan. All these, coupled with weak management of education at especially the basic education level are contributory to the menace of out of school children.

With proper planning, technicalities and bureaucracy can not to be contributory to the problem out of school children. Proper planning is one sure way of limiting the problems supposedly brought about by technicalities and bureaucracy. Building school and classes, for example, is never a solution to shortages. What is important in this regard is the reasoning behind and justifications for the actions. The only justification for building additional classes should be a valid statistics on needs, by region, by State, by Local Government, by zones, and by specific locations, and so on. This is the basis for planning which will, among other things, ensure that the right number and specifications of projects and the exact locations are adequately predetermined. With this type of statistics development will have the promise of being purposeful and of being specifically on target to rid the society the problem of out of school children.

4.5 Security Issues (SI):

Security challenges in the past fifteen years or so, is yet another causal factor for out of school children. The onslaught of the insurgents, for example, on especially schools, has necessitated school children to stay at home. School structures are not safe; where they seem to be safe the environment is not as at any moment the unimaginable and unfortunate may strike. School is an open system that has been deeply affected by the economic, political, and social conditions of the current state of the society. The pre-dispositional factors contributing to the attacks directed on schools are linked to the emergence of domestic terrorism. The attack by insurgents is one of the predisposing factors for out of school children.

To tackle the security problems in schools, it is of paramount importance to first diagnose the problems and then to search for system wide solutions. The school policies, decisions and the school support services are not sufficient in addressing the security challenges. We must work collaboratively with the select section of stakeholders in public and private institutions, to develop emergency plans. School administrators, staff, parents and students have to understand the critical roles to play in supporting security measures in school. All critical stakeholders must commit their resources together and establish an effective working relationship for the purpose of promoting safe school in collaboration with local law enforcement agencies.

5.0 Efforts at Stemming the Tide of Out of School Children

A number of efforts have been made by the local and international communities at ensuring quality education and by extension taming the tide of out of school children. Four different instances of international efforts have been cited as examples: 1948 United Nations Organization’s (UNO) effort of 1948; Education for (EFA) all by 2000; Millennium Development Goals (MDGs); and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). On the other hand, three local examples were cited from policies and laws such as: the 1999 constitution; 2004 UBE Act; and the National Policy on Education (1977; 1981; 1998; and 2014).

5.1 International Efforts

First example in the international efforts at ensuring that every child is in school and remain in school is the United Nations Organization, in its 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights which states in part, in article 26 that: Everyone has the right to education. That school should be free at least in the elementary and primary stages; and that Elementary education shall be compulsory, with technical and professional education shall be made generally available. It is clearly stated that education is a right of every child. This is the basis upon which every government must consider and prepare for adequate provision of free and compulsory education. The assumption here is that education is supposed to be free and compulsory at least at the basic and secondary levels in Nigeria. It is largely because this 1948 UN declaration has not been heeded that today we have out of school children, (Obanya, 2000).

It was perhaps in realization of the fact that the higher the percentage of out of school children the lower the potential for social and economic development that the United Nations mandated all member countries to ensure education for all by the year 2000. The World Conference on Education for All (EFA), held from 5 to 9 March 1990 in Jomtien, Thailand, was not a single event but the start of a powerful movement, whose main purpose was to address out of school children. Other objectives were: expansion of early childhood care and development activities; Universal Primary Education by the year 2000; improvement in learning achievement; reduction of the adult illiteracy rate to one-half its 1990 level by the year 2000, with sufficient emphasis on female literacy; expansion of provisions of basic education and training in other essential skills required by youth and adults; and increased acquisition by individuals and families of the knowledge, skills and values required for better living and sound and sustainable development. Some major meetings took place: in 1991 in Paris, in 1993 in Delhi, and in 1996 in Jordan, to review the progress made towards meeting those targets and to keep the EFA movement going. The reports left much to be desired, as EFA goals were far from being achieved and out of school children was already manifesting, (Adarechi, 2000).

The last meeting of the World Education Forum was held April 2000 in Dakar to review the assessment of the progress made during the decade and to renew the commitment to achieve the Education For all (EFA) goals and targets. All of us here are living witnesses to whether or not the EFA goals have been achieved in Nigeria. Some of the flimsy excuses for the failure to meet EFA goals in Nigeria and elsewhere centered largely on the focus. Nigeria and other countries were said to have focused on basic education to achieve EFA goals while the focus of Jomtien was on basic learning needs. According to Jomtien:

“these needs comprise both essential learning tools such as literacy, oral expression, numeracy, and problem solving and the basic learning content such as knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes required by human beings to be able to survive, to develop their full capacities, to live and work in dignity, to participate fully in development, to improve the quality of their lives, to make informed decisions and to continue learning” (WCEFA Declaration 1.1).

It was argued that basic education was not a clear cut generally accepted concept. It was left to countries to specify what they understood by basic education in their specific contexts. In consequence, Nigeria and many other countries took basic education to mean primary schooling or lower level education. Even if the focus of the Jomtien idea of Education for All was not on education systems per se but on learning in its broadest sense, it can be concluded that EFA goals have not in any way been achieved in Nigeria. Believe it or not, Nigeria’s failure to achieve EFA goals must be counted as part of the causal factors of out of school children in Nigeria.

As a follow up to the failure experienced by EFA 2000, MDG emerged with 2015 dateline. The Nigeria 2015 Millennium Development Goals End-Point Report presents a tacit summary of all the details about MDGs in Nigeria, (UNDP, 2015). It was mentioned that Nigeria was among the 189 countries from across the world that endorsed the United Nations Millennium Declaration in New York in September 2000, which led to the adoption of the eight time-bound Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and their monitorable indicators. The eight goals were to be achieved by respective countries by 2015. Goal number two, which was to: achieve universal primary education, is of particular importance here because it aimed at, among other things, reducing out of school children. The sad news is that MDG 2 which has as its main focus the achievement of universal primary education has not been achieved. The consequences are today visible on our streets,

The document mentioned that the net enrolment in basic education has had a fluctuating history of an upward trend to the mid-point assessment year. This positive trend was however halted in later years as a result of the disruptions brought about by so many things including insurgency. The insurgency in particular led to the destruction of many schools with the school children constituting a large size of the internally displaced population. Consequently, the net enrolment of 60% in 1995 declined to the end-point net enrolment of 54% in 2013. With respect to primary six completions rate which stood at 73% in 1993 trended upwards in most of the subsequent years culminating in 82% at the end-point year. The literacy rate trended marginally upwards in most of the years from 64% in 2000 to 66.7% in 2014. The significant rate of 80.0% achieved in 2008 could not be sustained. In short, this second MDG, like Education for All by the year 2000, has left much to be desired, (Garba, 2017).

With this very poor outcome in the achievement of especially MDG 2 as reported by the country report, the Post-2015 development agenda emerged. Nigeria was said to have committed itself resolutely to ensure the smooth commencement and implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Notable among such resolutions was the continuation with the unfinished business of the MDGs. The purpose was to meet implementation challenges in Nigeria. In the context of the SDGs, the document insisted on the need to devise additional strategies to overcome the many challenges that hampered the full attainment of the MDGs. Nigeria has therefore, in this regard developed a strategy that supported a smooth transitioning from MDGs to the SDGs anchored on some inter-related pillars which include, among others, creating institutions and making institutional arrangements for the SDGs; funding mechanisms and pathways; and capacity building and mainstreaming of the SDGs.

The post-2015 development agenda which was agreed upon by member States on August 2, 2015 during the United Nations Summit, conceptualized the 2030 agenda for Sustainable Development. The document announced seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (with additional one hundred and sixty nine targets) as follows: Goal 4 was to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. The 17 SDGs and the 169 corresponding targets, and especially SDG 4, have already come into effect since January 1, 2016 and the programme has a life span of fifteen years, up to 2030. With six years already gone, the questions now are how prepared is Nigeria and what is the current update in terms of implementation of the SDGs? Is SDG 4 good enough to address the problem of out of school children?

The corresponding targets of SDG 4 and which must be achieved by 2030 were stated as follows: Ensure that all school aged children complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education; Ensure that all school aged children have access to quality early childhood development to prepare them for primary education; Ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university; Increase the number of youth and adults who have relevant skills, including technical skills, for employment, decent jobs and entrepreneurship; Eliminate gender disparities in education and ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disabilities; Ensure that all youth and a substantial proportion of adults achieve literacy and numeracy; Ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote Sustainable Development; Build and upgrade education facilities that are child, disability and gender sensitive and provide safe, non-violent, inclusive and effective learning environment for all; Expand the number of scholarships available to developing countries for enrolment in higher education, including vocational training and information and communication technology, technical engineering and scientific programmes; Increase the supply of qualified teachers, including through international cooperation for teacher training in developing countries. These corresponding targets of SDG 4 are good enough to address many problems in education, especially the issue of out of school children (Emon & Okpede, 2000). The main question is, what have we done so far in this regard to raise hopes for out of school children?

5.2 Local (National) Efforts

First and most important consideration in the municipal efforts at ensuring that every child is enrolled and remains in school is the Constitution. The 1999 Constitution, Section 18 (3) states that: Government shall strive to eradicate illiteracy, and to this end government shall and when practicable provide, among others: Free, compulsory and universal primary education; Free secondary education; and so on. This is yet another basis from which government must provide free education. The assumption here is that from the point of view of the 1999 Constitution, education is supposed to be free and compulsory at least at the basic and secondary levels in Nigeria. If this aspect of the constitution has been adequately implemented the problem of out of school children would have been reduced to the barest minimum. Unfortunately we only hear of constitutional breach only when personal and often selfish interests are affected.

The Universal Basic Education (UBE) Programme was introduced in 1999 as a reform programme to among other things address mass enrolment, ensure greater access to quality basic education and reduce the scourge of out of school children. The UBE Act of 2004 provides for free and compulsory education for children of primary and junior secondary school age in Nigeria. The policy is aimed at providing greater access to and ensuring the quality of basic education throughout Nigeria. The main objective was to among other thing ensure an uninterrupted access to 9-year formal education by providing free and compulsory basic education for every child of school-going age. It was also meant to reduce out of school children. Despite the good intentions of the law, several loopholes have been discovered based on some realities on the ground. For example, the number of out-of-school children is still outrageous. If the provisions of the UBE Act have been adequately implemented the problem of out of school children would have brought to the barest minimum.

From the policy level, the National Policy on Education (FGN, 2014) states clearly that: “in pursuance of the above objectives of primary education, Government has made primary education free and universal…” Primary education is not only an inalienable human right – it is a powerful instrument for generating benefits for individuals and their families, the societies in which they live, and future generations.

In spite of these cited examples: four from international scenes, such as the 1948 United Nations Organization’s (UNO) effort of 1948 on right to education; Education for (EFA) all by 2000; Millennium Development Goals (MDGs); and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). And another three examples form local efforts, such as the 1999 constitutional provision of free and universal free education; the UBE Act of 2004; and the NPE provision on free and universal primary education. Nigeria has yet to control the escalating scourge of out of school children. In addition there are other deceptive or ill-conceived programmes introduced at regional and later State levels which abolished the payment of school fees. The removal of school fees or other related levies does not make education free because there are still other constraints to the child’s access to education (FGN, 2000).

6.0 Premises for Tripartite Policy Framework

We feel the need for some decisive actions against the menace of out of school children. Preparing grounds to confront a problem can only succeed if the process is well planned. Planning is an essential prerequisite for success, especially in education. Constituting part of the planning process is the promulgation of policies targeted towards addressing the menace of out of school children, yes, policies! We need a policy to implement policies as much as we need proper planning. Policies for taming the menace of out of school children have to be discerning and diversified. Such policies should be seen from the point of view of stakeholders with government leading the process. Here three different levels of premises for policy framework are advocated. There has to be a clear policy on the implementation of extant laws and existing policies on education. The issue of out of school children is, more or less, either a direct consequence of the seeming neglect of existing laws and policies or a direct trigger of the problem. There has to be, for example, a policy of no more policies on education until all policies are satisfactorily implemented. Secondly, there has to be a policy on the present conditions of our learning spaces that is both the school environment and the classes. This policy is to be geared towards creating an ideal school. The last level being advocated for policy formulation is from the point of view of empowerment of some select forces and local authorities to check the excesses of defiant and compromising parents.

6.1 First Premise for Policy Framework: Extant Laws and Existing Education Policies

Certain historical antecedents have impacted on how educational policies are formulated and implemented today in Nigeria. The colonial administration administered education through ordinances codes. These codes and ordinances were used as guidelines for the administration of education. Such ordinances and codes served as the basis for the modern day educational policies, education laws and techniques of educational administration in Nigeria, (Fabunmi, 2003). Below is a summary of such laws and they were strictly implemented.

Laws, Ordinances, Edicts and Laws: Legislations in education have always been used to address issues to ease and direct administration. In Nigeria this began with the 1882 education ordinance for British West Africa, (Lagos, Ghana, Sierra Leone and Gambia). The most notable prescription of this ordinance was the annual evaluation of pupils, a system of grant-in-aid, and the establishment of a General Board of Education. The 1887 education ordinance was a purely for Nigeria. It created an Education Board and standards of examination. The 1916 education ordinance was a result of Lord Lugard’s efforts to cater for the whole country. The ordinance recommended increase in budgetary allocation to education. The ordinance paved way for full cooperation between the government and the missions. The 1926 education ordinance was based on a memorandum on Education Policy in British Tropical Africa. The need to provide an operational guideline for the memorandum provided the impetus for this ordinance. The ordinance was a significant landmark in education in Nigeria and an outcome of the recommendations of the 1920 Phelps-Stoke Commission on Education in Africa. The report paved the way for the first educational policy in 1925. The 1948 education ordinance originated from the report of the Director of Education who was appointed in 1944 to review the ten years plan. This led to the promulgation of the 1948 education ordinance. The ordinance created a Central Board of Education and four Regional Boards of East, West, Lagos and North. The 1952 Education Ordinance was introduced to enable regions to develop their educational policies. The ordinance became an education law for the country, (Fabumi, 2005).

The Ashby Report of 1959 was set to investigate Nigeria’s manpower needs for a period of twenty years (1960-1980). The Commission led by Sir Eric Ashby, recommended for the expansion and improvement of primary and secondary education, the upgrading of the University College at Ibadan to a full-fledged university and the establishment of three other universities at Nsukka, Ife and Zaria. It also recommended the establishment of University Commission in Nigeria so that the universities will maintain uniform academic standard. The post-secondary school system was to produce the post-independence high-level manpower needs of Nigeria, (Osokoya, 2002).

The Federal Military Government of Nigeria enacted Decree No. 14 of 1967, which created twelve States and subsequently to nineteen States in 1976. Each state promulgated an edict for the regulation of education, and its provision and management. Each state amended its education law when necessary. All the edicts had common features, such as state take-over of schools from individuals and voluntary agencies, establishment of school management boards and a unified teaching service. The first era of military rule (1966-1979) in Nigeria was followed by the second republic. With the return of military administration in 1983, several decrees were promulgated by the Federal Military Government to guide and regulate the conduct of education. Such include, Decree No. 16 of 1985, which was promulgated on National Minimum Standards and Establishment of Institution’s, Decree No. 20 of 1986 which changed the school calendar from January to December to October to September,.

This historical analysis of educational policy formulation in Nigeria has a lot of implications for both educational planning and policy. Most of the colonial educational policies had the shortcoming of not taking into account our local peculiarities and not involving Nigerians in their formulation. It is also essential to integrate all the good parts of earlier education policies, whether colonial or post-colonial, into any proposed education policy. The participatory model of planning education and formulating educational policies is the most appropriate for a multi-ethnic nation like Nigeria, (Fabunmi, 2003). In order to minimize conflict and protest, it is good for both educational planners and policy makers to involve adequate representatives of the society, particularly stakeholders in education, in educational planning and policy formulation.

It is evident that education in Nigeria has all along been managed through laws. We have seen examples of how laws in education were enacted and implemented. It is clear that education requires a set of rules and regulations to guide actions of educational actors for effective implementation of laws and policies and generally for the implementation of curriculum. As a result of its dynamic nature the Nigerian education industry must continue to reel out laws to back it. There is the need to moot out policies for adequate implementation of the national policy on education (NPE) and other extant laws. 1999 Constitution of Nigeria, all States’ education laws, and local boards of education must have implementation policy, as they relate to the rights and responsibilities of students, especially at lower levels of education. This is why the constitution, laws edicts, ordinances, decrees and policies which derive from the core value of the society provide the legal framework upon which individual corporate and institutional activities and conducts are monitored. The school, which represents the society’s system for the transmission of formal education, is by no means an exception to the regulatory provisions of the society in the fulfillment of its goals. The school with its members and activities are thus regulated by constitutional principles and provisions for its effective organization, administration and performance of its complex and essential functions (Akinkpelu, 2009).

Constitutional Provisions on Education: The Macpherson Constitution of 1951 put education in a concurrent list, hence both the central and regional governments could legislate on education. This has a lot of impact on the present arrangement. There are thirty-six state governments and the federal government in Nigeria, each of which could legislate on education.

The objectives of education as provided in chapter II, Section 18, Sub-Sections 1-3 of the 1979 constitution included, among others: free, compulsory and universal primary education; and free secondary education, FGN, 1979). The 1979 constitution put education in the concurrent legislative list. This implies that responsibilities and authority in the provision of education ought to be shared among the three tiers of government, that is, federal, state and local governments. Chapter 11 of the constitution gave the federal government more powers than the states in the areas of post primary, professional, technological and university education under its control. The states had total control of primary; post primary, technical, technological, university and other forms of education within their territories. The Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (Promulgation) Decree of 1999, chapter 11, Section 18 re-states the objectives of education in Nigeria as contained in the 1979 constitution of Nigeria and the third edition of the National Policy on Education (FRG, 1998).

The 1999 constitution, extant laws and existing policies on education in Nigeria are the main basic legal documents. Even after independence Nigeria modeled its constitution after the British parliamentary political system, (FGN, 1999). It was not until 1979 that, Nigeria changed and modeled its constitution after the U.S.A., and it prescribed a presidential system of government. Each of these constitutions has made provisions for education. In fact, the Macpherson constitution of 1951, not only provided for education in Nigeria, but also regionalized the administration and control of education. Consequently, in the 1999 constitution, the commitment and obligation of Nigeria to education are clearly spelt out under the heading: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy, Section 18 of the constitution states the government’s educational objectives and the degree of its commitment to a policy of educational accessibility and adequate scientific and technological orientation and eradication of illiteracy as follows: Government shall direct its policy towards ensuring that there are equal and adequate educational opportunities at all levels, and; Government shall promote science and technology; Government shall eradicate illiteracy, and when practicable provide: (Free, compulsory and universal primary education; Free secondary education; Free university education; and Free adult literacy programme), (FGN, 1999).

It is evident in these examples of constitutional provisions that education has all along been of primary interest and concern. Furthermore, it is part of the obligation of government to provide facilitative grounds for the education for its citizens. It is essential also to note that it is the intent of most governments to provide free education at all levels. In other words, government can embark on the provision of free education when government has the will and the means to sustain such efforts. Most importantly, the source of the rights and obligation of the Nigeria government and its citizens to provide and participate in education stems from the 1999 constitution.

If it is historically evident that education in Nigeria has all along been managed through laws and that laws in education have been enacted and implemented; and again if it is evident from Macpherson constitution of 1951, 1979 and 1999 constitutional provisions that education has all along been of primary interest and concern: why is it difficult now to implement already enacted laws; why is it difficult today to respect the constitutional provisions on education?

6.2 Second Premise for Policy Framework: Ideal School

To be able to remedy the menace of out of school children schools must first be made available, not just any school, but an ideal school. An ideal school has several essential components: structure; infrastructure; educational support facilities, adequate number and quality of teaching and non-teaching workforce; management structure and reporting system. School must be resolutely modern in architectural style/form and must be surrounded by carefully considered and planted grounds. In recognition of the ethical values promoted by the school, the building itself has a high environmental rating in its construction and maintenance of internal environment. There must be glimpses of gardens and greenhouses that are to be tended by pupils. In an ideal school, the notion of an outdoor curriculum is strong and students have a range of activities to choose from – the outdoor curriculum includes, but is not defined by, activities based around sport, (Edgerton, & Ewen, 2011).

An ideal school has several essential components: structure; infrastructure; educational support facilities, adequate number and quality of teaching and non-teaching workforce; management structure and reporting system. Structure comprises of the school as a whole, inclusive of the classes and all other buildings. Structure as a component of an ideal school includes arrangement of all buildings in terms of alignment to the environment and to each other. School structure is usually arranged in accordance with an approved plan which must take into cognizance the main purpose of the buildings, the physical and other characteristics of the potential users, the climatic conditions, and so on.

Related to school structure is the infrastructure. It refers to all education infrastructures which are crucial to learning environments. It comprises of the entire school buildings, classrooms, laboratories, and equipment. There is a strong evidence that high-quality infrastructure facilitates better instruction, improves student outcomes, and reduces dropout rates, among other benefits. For example, a recent study from the U.K. found that environmental and design elements of school infrastructure together explained 16 percent of variation in primary students’ academic progress, (Cox, 1996). This research shows that the design of education infrastructure affects learning through three interrelated factors:naturalness(e.g. light, air quality),stimulation(e.g. complexity, colour), andindividualization (e.g. flexibility of the learning space). Education infrastructure includes suitable spaces to learn. This is one of the most basic elements necessary to ensure access to education. School classrooms are the most common place in which structured learning takes place with groups of children. While learning also takes place in a variety of different types of spaces – tents, temporary shelters, shade of trees, mosques, and so on – families and communities expect formal education to take place in classrooms that have been designed for safety and comfort. Some of the attributes of adequate infrastructure are: Sufficient space per child, sufficient space for the right number of children per classroom, ensuring safety of children in school, adequate separate sanitary facilities for boys and girls and for staff; water and electricity; and possibly internet connectivity. Facilities may be inadequate in many ways, including being over-crowded, lacking in adequate sanitary facilities and lacking water for hygiene. The health implications of inadequate toilets and sanitation are very serious. Girls in particular are pushed out of school if facilities are inadequate.

Educational support service facilities provide a variety of services for students to discover their individual academic skills and to become self-sufficient, life-long learners. The provision of educational support facilities has received an emphatic mention in the NPE (2014). Educational support facilities can be understood from three broad divisions: learning support service facilities; teaching support service facilities; and students’ welfare service facilities. Learning support service facilities include well stocked school library, adequate relevant text books; writing materials, and so on. Teaching support service facilities include resource centre, laboratories, workshops, public address system, and so on. Students’ welfare support facilities include school meals (school feeding programme), school uniforms, health (dispensary or clinic) and nutritional facilities, and other incentives (Elbom, 2012).

Another important component of an ideal school is the supply of adequate number of qualitative teaching and non-teaching workforce. No matter how good school structural and infrastructural facilities appear to be, it will be of no value if teachers do not seem to understand their relative usefulness. Teachers are the most important component of an ideal school. Next to teacher in terms of importance in the school setup is the management structure and a transparent reporting system. An ideal school must be seen to be compliant with NPE provisions on Guidance and Counselling.

6.3 Third Premise for Policy Framework: Empowerment

Empowerment has been the subject of widespread and often thoughtful and careful theorization. Unfortunately, it also became an overused word in policy circles. To many, it is used for the purpose of co-opting or placating people. The aim here is to reveal, identify, and clarify its utility and importance for political and civic leadership. The question is actually on the meaning of empowerment. Empowerment has been defined and measured in many different ways. Empowerment has been defined as an intentional ongoing process centered in the local community, involving mutual respect, critical reflection, caring, and group participation, through which people lacking an equal share of valued resources gain greater access to and control over those resources. It is also seen as a process by which people gain control over their lives, democratic participation in the life of their community, and a critical understanding of their environment (Perkins & Zimmerman, 1995). The common elements in those definitions are that empowerment is a process; it occurs in communities; and it involves active participation. In this context empowerment is viewed as a goal or outcome of participation. It is a key part of the process of both developing and applying political and civic leadership. Empowerment is a collective rather than just an individual process. Empowerment through participatory action with others is, in fact, one of the most effective ways to master one’s fears, obsessions, or disdain for self or others. But think of those as side benefits because empowerment is mainly about working together for our shared interests, to improve our communities and institutions, and build a better society (Perkins & Zimmerman, 1995).

Currently there is no policy for empowerment, there has to be a one, that will clearly empower school neighborhood, Parents-Teachers’ Associations (PTA), Old Boys Associations and the traditional authorities, on one hand, and local law enforcement outfits (such as Hisbah Board) on the other, have participate in all school and related activities with relative authority. They can be of great use in the amelioration of out of school children.

7.0 School Counselling as a Supplementary Remedial Measure for Taming the Scourge

Reducing the number of out of school children has to be approached from multi sectoral efforts. It has to involve governments, the private sector, the media, the communities and professional helpers. The government has to intervene with policies and the political guidance; the private sector has to help with logistics and financial support; the media has to intervene with public enlightenment; and the communities have to resolutely participate in policy implementation. More importantly, the professionals, mainly the school counsellors will have to give some interventions to keep children in school, to make streets unattractive for the children and also to devise ways of rewarding school attendance.

School counselors, as human development experts that employ psychological, sociological and human development theories, must help school system with an in-depth analysis of out of school children in order to make interventions easy. School counsellors must be ready to build evidence and analyse high impact interventions for children. As professional helpers school counsellors must generate and document knowledge about possible ways of tackling out of school children for dissemination to relevant stakeholders. The main focus of school counselling in this regard should be to make learning interesting and purposeful so as to be able to retain children in school. Counsellors must therefore provide all stakeholders with support to strengthen all programmes for the improvement of access to and retention in school. This will undoubtedly reduce the number and magnitude of out of school children, (Morrissey, 2015).

Owing to huge competition and expensive education system, parents pressurize their children to perform well by packing them into a room with books and switching off the television sets, internet connectivity and reducing the time for sports and other outdoor activities. But this does not seem to work. Instead of helping, this only makes children depressed. Children are made to hate schooling. It also constitutes some burdens in the fulfillment of expectations of their parents. Counselling helps in this regard can assist the child in a proper direction so that he/she can be very much aware of what he/she wants to do in life, (Anyabolu, 2013).

Parents still believe in bringing good grades to get their children into the best tertiary institution to study a predetermined field of study that will give them a successful career. It is however, important to know the interests of children. Here the school counsellor plays a vital role. With broad career options, school counselors need to equip the child with all recent trends, current developments in different streams, demands and financial prospectus giving priority to the child’s interests. Counselling sessions at an early age opens the lines of communication making children familiar with the importance of choosing the right career. A regular counselling session is about listening to the child and giving respective suggestions.

Out of school children or official out of school children are usually excluded from learning opportunities and are usually the most vulnerable group for underworld activities. The ‘official out of school children’ are easy to locate but the actual out of school children are very hard to reach. Both types of out of school children are usually from poor backgrounds and sometimes they have to help with the domestic chores to support the family. While the government is generating home-grown data for purposes of policy formulation, the school counselors must target their interventions for every child to be in school, to remain in school and to gain some knowledge and skills (Nwabachili, 2016).

8.0 Conclusion

Discussions have all along been on the need to evolve an effective policy that can pave the way for authoritative judgment and for the establishment of a basis for administrative actions toward taming the scourge of out of school children in Nigeria. A framework has been proffered, discussed and presented, with a three broad sections: first aspect of the policy framework is implementation of extant laws and existing policies on education and its delivery; second leg of the policy framework is the transformation of learning spaces (what we today call schools) to the status of ideal schools; the third led is empowerment of stakeholders to own the dual projects of implementation (of laws and policies) and the transformation of schools, and also to voluntarily and actively participate in all other education related projects.

In addition to such policy framework, three additional recommendations are considered vital in all efforts to tame the scourge of out of school children in Nigeria. First is the issue on the need for uniformity of policies and implementation procedure across States. Unless States collaborate on the issue of reducing out of school children, efforts by individual States is not likely to see the light of the day. Whatever policy is put in place the understanding and cooperation of the neighbouring States must be sought. In other words neighbouring States must be taken along for any policy on taming the scourge of out of school children to succeed.

Second recommendation is on the free education project. Nobody is doing anybody a favour by providing free education. It is a constitutional right. Free education project is another sure way of ridding the society of the menace of out of school children. It must be reiterated however that, it will difficult if not impossible for government to succeed if it ventures into it without stakeholder participation. Government singular sponsorship of the free education project without active stakeholder participation has never happened anywhere. Discussion with especially parents and other stakeholders on the project and sharing of responsibilities is an important pre-requisite for success. Provision of education is a collective responsibility. Government and all other stakeholders must have a round table discussion to forge understanding and cooperation, and to share responsibilities. In addition government must put in place machinery for monitoring compliance and implementation.

If government at whatever level, or anybody for that matter, is genuinely interested in ridding this part of the country of the menace of out of school children, this third recommendation must be given due cognizance. This part of the country has a long history, spanning several centuries, of cherishing and embracing Islamic values and generally Islamic ways of life, inclusive of Islamic system of education. Any policy or law or any project in education that seems to relegate this fundamental concern to the background will surely continue to meet stiff opposition. In short, unless our value and value orientation are respected, incorporated and given due cognizance taming the scourge of out of school children will continue to remain a mere fantasy.

Referencess

Adarechi, B.C. & Romaine. H. A. (2002). Issues, Problems and Prospects of Free Compulsory and qualitative Education in Nigeria. Onitsha: Nigeria Educational Publishers Ltd.

Akinpelu J.A. (2000) “Looking Forward: Nigerian Education in the 21st Century”. A key note address presented to the 18th Annual Conference of the Philosophy of Education Association of Nigeria (PEAN) at University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Oyo State on 17th October.

Anyabolu C.L (2000). Basic Education for Productivity and Enhanced National Economy. Journal of Vocational and Adult Education. 2(1) UNIZI K Awka

Coombs, P. (2011) the World Educational Crisis: A Systematic Analysis. Lagos: University Press.

Cox, C. (1996). “Schools in the Developing Countries” Education Forum, 1(2).

Edgerton, S., Ewen, A. A. (2011). Schools and Schooling in Sub-Saharan Africa. Vol. II (5).

Elboim-Dror, R. (2012) “Some Characteristics of the Education policy formation system” in Policy Sciences Vol. 1(2).

Emon. E.O. and Okpede, E.O. (2000). The meaning, history, philosophy and lesson of UBE. Proceedings of the 15th Annual Congress of the Nigerian Academy of Education. University of Benin 6-9th Nov.

Fabunmi, M. (2003). Social and Political Context of Educational Planning and Administration, Ibadan: Distance Learning Centre, University of Ibadan, Ibadan

Fabunmi, M. (2005). Historical Analysis Of Educational Policy Formulation In Nigeria: Implications For Educational Planning And Policy. International Journal of African & African American Studies Vol. IV, No. 2, Jul 2005

Federal Ministry of Education (2000). Implementation Guidelines for Universal Basic Education (UBE) Programmes. Abuja: Federal Ministry of Education.

Federal Republic of Nigeria (2014). National Policy on Education. Lagos: NERDC Press.

Federal Republic of Nigeria (1979). The Constitution of the Republic of Nigeria, Lagos: Federal Ministry of Information.

Federal Republic of Nigeria (1999) Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. Apapa Lagos; Federal Government Press.

Garba, A. (2017). Nigerian educational System and the Sustainable Development Goals: Problems and Prospects. A Lead Paper Presented at the First International Conference, organized by Faculty of Education, Yusuf Maitama Sule University, Kano: Nigeria

Morrissey, M. (1996, January). The transition from counseling student to counseling professional. Counselling Today, p. 14.

Nwabachili, .C.C (2000) “The Universal Basic Education, Myth or Reality”. A paper read at the 18th Annual Conference of the Philosophy of Education Association of Nigeria (PEAN) October 17th at the University of Ibadan, Oyo State.

Obanya, P. (2000). Education and the Nigeria society: revisit the UBE as a people’s oriented programme. Being the 2000 Prof. J. A. Majasan first anniversary memorial lecture, Ibadan

Osokoya, I.O. (2002). History and Policy of Nigerian Education in World Perspective, Ibadan: AMD Publishers

Perkins, D. D. & Zimmerman, M. A. (1995). Empowerment Theory, Research and Application, in American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), P. 569, Research Library Core.

UNDP (2015). Nigeria 2015 Millennium Development Goals: End-Point Report

World Conference on Education for All (WCEFA), (1990). Meeting Basic Learning Needs – Final Report (UNICEF – UNDP – UNESCO – WB – WCEFA, 1990, 129 p.)